The Hydrogen Fuel Cell Car: A Bumpy Ride to a Cleaner Future

One driver’s three-year experiment with an imperfect but promising technology

Photos by Scott Lerner

It’s a hundred degrees in Hollywood on the first Saturday of October.

With 11 miles left on our tank and a 35-mile trip ahead of us to get back home, my wife and I pull our Toyota Mirai hydrogen fuel cell car into a busy ARCO at the corner of Hollywood Boulevard and Wilton Place.

Beyond the gas pumps, on a sliver of asphalt abutting an alleyway, we find what we’re looking for: a True Zero hydrogen station, with its distinctive blue-and-white awning arcing into the hot sky.

Two cars are ahead of us, one parked atop a painted blue rectangle that reads “True Zero Fueling Only.” There’s only one pump at this station, so we must wait in line to refuel. But that’s fine. We are used to waiting.

After a few minutes of no movement, I notice that the lead car has not yet begun to fuel. In fact, the nozzle isn’t even attached to the vehicle. We shift in our seats, rubbernecking to see what the holdup is. I check the station’s status on h2-ca.com—a site developed by fuel cell driver Doug Dumitru to monitor “not only stations that have fuel but whether they are likely to still have fuel when you get there.” H2-ca.com reveals that in the 30 minutes it took us to drive from Claremont, a Los Angeles suburb, to Hollywood, the station has for some unnoted reason gone from online, with enough fuel to fill the tanks of at least 25 cars, to offline.

“Did you check before we left the house?” my wife asks.

The answer is yes, almost obsessively. I’ve navigated to h2-ca.com so frequently over the past three years that my phone recognizes it as one of my most-viewed sites. It’s now an official Siri suggestion, alongside Google, The New York Times, and a reminder to text my mom.

I see a technician working on the backside of the pump, which gives us hope. Then the lead car departs without having refilled—an ominous sign—and I wonder if this will be the one time, in 34 months of driving one of the nearly 9,000 hydrogen fuel cell cars on California roads, that I finally run out of fuel.

*

I was a teenager in 2003, when President Bush called for investment into zero-emission “hydrogen-powered automobiles.” The following year, Governor Schwarzenegger kicked the ball downfield by proposing a Hydrogen Highway for California. His plan called for lining the state’s existing, well-traveled routes with hydrogen refueling stations. Cars driving those highways would look and perform just like normal cars—only five minutes at the pump would afford the driver 300 miles of range. But these cars would run on hydrogen, a fuel touted for its abundance atmospherically—and commercially—and for the fact that tailpipe emissions amount to a trickle of water.

The technology fascinated me. Though I’d developed a passion for classic American muscle cars growing up, the coming climate crises figured heavily into my consciousness. 2003 was the year the Cedar Fire claimed dozens of victims as they were attempting to escape in their cars. An Inconvenient Truth reverberated in our household, prompting spirited dinnertime discussions. Protestors at my high school chanted “No War for Oil” as the US prepared to invade Baghdad. In 2005, Hurricane Katrina and its horrific aftermath foretold a perilous future.

Hydrogen, alternatively, promised cleaner air in our cities and would cut the tether to oil, reducing CO2 emissions. Particularly in Southern California, hydrogen offered an environmentally friendly way to navigate the infamous urban sprawl that necessitates a car to get around with any sort of reliability.

By 2018, I’d forgotten all about hydrogen fuel cell cars. I drove a hybrid and drafted lengthy, impassioned emails to my landlord, attempting to persuade him to upgrade our property’s breaker to support the installation of a 240-volt electric car charger. Then I saw a Mirai on the highway. I assumed it must be an experimental vehicle out for a real-world test, but no: An internet search revealed that California’s Hydrogen Highway was beginning to take shape around me, in Orange County, and in the urban centers of the state. Nearly 40 stations were a part of an emergent network—the largest of its kind in the world. I consulted the California Fuel Cell Partnership’s map of stations and discovered that I’d pass four on my way to work at UC Irvine, where I teach a writing class that focuses on climate advocacy. It thrilled me to learn that even without access to a 240-volt charger, I could still drive a zero-emissions vehicle. I wanted in.

I was so excited after I leased my Mirai—replete with HOV access stickers, a $5,000 state government rebate, and a $15,000 prepaid card to cover the cost of fuel for three years—that I started a blog to chronicle my participation in California’s hydrogen vehicle experiment. I made the car an Instagram account, as if it could be photographed at the slopes or beach or park, like a dog. Over the course of three years, I planned to visit as many stations as possible.

Under the hood, Car and Driver explains, the “Mirai is powered by what’s called a fuel-cell electric powertrain, meaning that hydrogen (which could actually come from cow manure, among other sources) is converted into electricity by the on-board fuel cell—essentially a chemical laboratory on wheels.” Hydrogen is stored in two bulletproof tanks beneath the carriage of the car. (Video that proves the tanks are in fact bulletproof posted to blog? Check.) Advocates hope that this same reaction will one day provide reliable power to much larger endeavors, such as semi-trucks, barges, trains, planes, and even cities.

This diagram from the Toyota Mirai technology brochure explains how the fuel cell system works. | Courtesy of Toyota

Mirai means "future" in Japanese, and indeed this is the first car of its kind to be brought to the general market. For the driver—a “trailblazer,” to use Toyota’s marketing term—the car itself feels less futuristic and more like a very nice sedan produced by a company with a reputation for producing very nice cars. Trailblazing implies that uncharted territory lies ahead and that someone is charting it. For me, this initially appeared to involve contending with a limited number of stations—that is, not a station at every freeway exit or just around the corner from my house. However, I began learning about the truly experimental nature of the endeavor the first time I attempted to refuel the car.

It was eight at night. I’d checked the Station Operational Status System (SOSS) website before heading to the UCI station after work and then checked the station status again as I stood in front of a pump that read “see attendant.” Only I was in a parking lot on the outskirts of UC Irvine’s campus. This was not a gas station, and there certainly were no attendants nearby. Out of curiosity, I swiped my Mirai fuel card. Nothing happened. Then I called Air Products, the company that operates the station. A nice person on the other end of the line confirmed that the pump was, in fact, offline, and had been so for some time. No one had reported it to them, and so they hadn’t reported it to the SOSS—the only way the news could have reached me.

When similar incidents happened with greater frequency, and eventually with regularity, I wondered if I’d entrenched myself in something far thornier than I’d realized.

Shane Stephens, founder and CDO of True Zero, acknowledges that there have been substantial infrastructural “growing pains.” The primary issue seems to be streamlining the mechanisms of producing and delivering fuel to stations. More than half of the state’s stations are operated by True Zero’s parent company, First Element, which does not produce or distribute fuel. For most of my time as a driver, that task has fallen to Air Products, a publicly traded company that “provides atmospheric gases, process and specialty gases, equipment, and services worldwide.” (Its support staff is always pleasant and informative, I should add.) Other station operators include Air Products, Air Liquide, Iwatani, and Shell.

“The number one cause of downtime,” Stephens told me when I called him last February, was that “stations were running out [of fuel] on a regular basis.”

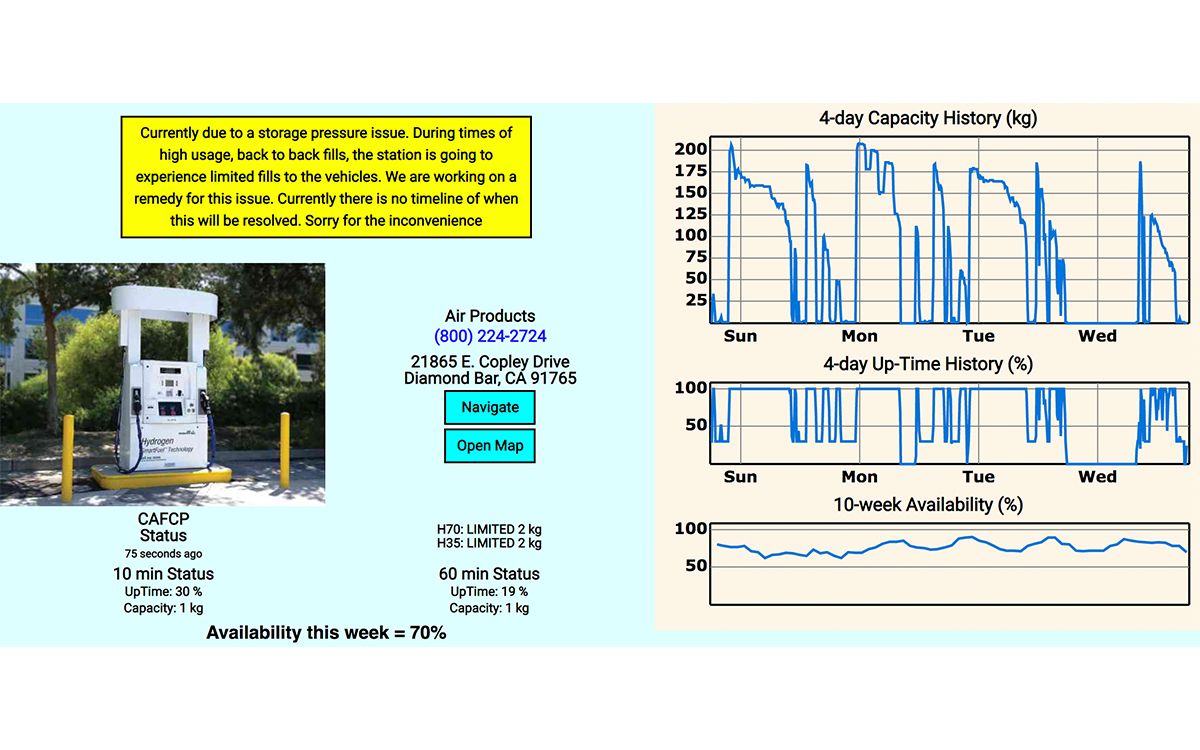

A screen capture of the Diamond Bar station, which shows that it is experiencing a technical issue.

As of this writing, there are 42 hydrogen fueling stations in California. Most are located in L.A., Orange County, and the Bay Area. At any moment on any given day, roughly 25 to 50 percent of stations are offline. (The week of October 19 saw 78 percent “statewide availability” according to h2-ca.com.)

But there have also been other issues, each adding some disruption to my life and the lives of other drivers. Some 3,500 in the Bay Area were severely impacted during an incident in June 2019, when a fire at an Air Products facility disrupted the hydrogen supply for months. The event became known, in the Mirai Owners Facebook group, as the Hydropocalypse.

Often there are long lines at popular stations, most of which operate, like the one in Hollywood, with one pump, serving one customer at a time. Waiting for three or four people to fill ahead of you can extend what Toyota promises to be a three- or four-minute fill time to half an hour or more. Then there are the nozzle freezes, which can take a minute or 10 to defrost.

Nozzles can freeze during refueling, though new nozzles now in use aim to reduce or eliminate the problem.

Compressors have to keep the hydrogen at sub-freezing temperatures. On hot days a station not designed to keep up with current demand can require a two- or three- or five-minute compressor reboot between fills. During my first year driving the car, station status updates did not register this downtime as temporary. Unless you monitored a station over the course of at least 15 minutes—the time between updates to the site—you could easily mistake a “temporarily down” station for an empty or malfunctioning one. This happened often to me. I’d be driving to a station that appeared online, only to arrive and find it offline. Before understanding this problem, I’d drive off, frustrated by the wasted trip and the wasted fuel.

*

At the Hollywood station, we’re still second in line. The technician has disappeared into a building behind the pump. The driver of the Mirai ahead of us steps out and shields the pump’s screen with his hand. He then turns to us and shrugs, hands expressing what’s hidden behind the surgical mask.

“So I guess the station’s down?” my wife asks, sardonically.

I apologize before turning off the car to preserve what little fuel we have left. The heat is oppressive, especially when wearing a three-ply cotton mask. We open the doors and grow increasingly irritated—and worried.

“We might really need a tow,” I say, imagining all the ways being towed is going to be an enormous and potentially dangerous endeavor in the time of COVID.

(I know what you’re thinking: Why did you let your tank get so low? Amateur move! Well, the station nearest to my house, Diamond Bar (15 miles distant), was offline that morning due to a mechanical issue. Another station that was closer is now permanently closed. According to Keith Malone, who runs communications for the CAFCP, that station was operated by “thoughtfully funded small business owners” who struggled with maintenance and upkeep.)

I step out of my car to find some shade and chat with the driver ahead of us. He reports that he’s “on zero.” He wouldn’t even make it to the Fairfax station four miles southwest. I tell him I’m thinking about heading there.

“Allegedly they have plenty of fuel,” I say, “but if I make the trip and can’t refuel, I’m four miles farther from my house and equally stranded.”

He nods. He knows.

We continue to chat at a distance. Sure, his plans have been delayed. But this young guy appears inured to and at peace with the inconvenience. Like us, he has no choice but to wait.

*

It’s important to note that the Hollywood station is part of the old guard: a spate of “stations not set up for market growth,” according to Stephens. A new station in Fountain Valley, where four cars can refuel simultaneously, is a rather encouraging example of what the near future holds. Because of increased storage capacity, the station can comfortably provide fuel for 400 cars per day. This is a tremendous leap forward. A new nozzle in use there should reduce freezing events. I’ve tried it, and it is a marked improvement. It’s also a beautiful station where hydrogen pumps take up almost as much real estate as those dispensing gasoline. The station relies on liquid hydrogen, which is stored onsite and requires fewer deliveries per week. And, to avoid future hydropocalypses, “every new station has to have a second backup source of hydrogen,” according to Malone.

“We’ll be in good shape in 12 to 18 months,” Stephens assured me back in February. His company is “aggressively deploying the learning of those growing pains.”

Toyota plans to release the second-generation Mirai soon. Honda is likewise taking big steps towards hydrogen, as are other major players like Shell (think of that what you will). Infrastructure is expanding in Germany, England, Japan, South Korea, and Hawaii. Saudi Arabia is looking toward a hydrogen “new future.” State policy here in California outlines plans to fund 100, 200, and even 1,000 stations capable of serving 1 million vehicles. These policies envision a viable path for hydrogen alongside electric vehicles, each serving different drivers in different circumstances—especially those without access to electric chargers or who can’t wait for long charging times. Stephens reports that by 2030 the market will be able to “sunset all government support.” California is the leader in deploying and testing this technology right now. There’s no denying that what’s happening here will inform all future hydrogen expansion throughout the world. Already, the Orange County Transit Authority is debuting a hydrogen bus fleet pilot program.

But older stations are still the backbone of today’s network. Some have notable reliability, staying online almost 100 percent of the time during any given week. Others hover around 50 or 60 percent uptime. It’s sobering to learn that new stations can take 18 months to construct if, as Malone told me, “everything goes as planned.” Each can cost well over a million dollars. This is to say that change comes slow to the hydrogen highway, and with a hefty price tag.

*

Twenty minutes later, with a line of cars snaking into the street, the onsite technician joins us near the pump and explains the problem. On a hot day, the compressor could not stay cool. He had been adding coolant, hoping to help it along.

My Mirai, second in line. The True Zero technician talks to a driver and explains the issue the station is experiencing.

“Do you think we’ll be able to fill up?” I ask.

“I won’t leave until everyone has refueled,” he says, gesturing toward the five cars that had formed a line snaking dangerously into the street. “I’ll be here until I can get you all on your way.” He wears an overshirt in the heat and talks about working overtime because there are essential workers, doctors, and nurses who rely on their cars to get to the hospital and save lives. Right. I thought, they rely on transportation just as we rely on them. They have no time for faulty compressors, frozen nozzles, or late deliveries of hydrogen. I am reminded of the days when I wasn’t working from home, when hunting for fuel or futzing with a frozen nozzle was near the bottom of my list of enjoyable after-work activities.

For the car ahead of us, the pump works slowly but eventually provides three kilograms, which is about a three-quarter fill. Then it’s our turn. The technician stands beside the pump as I swipe my card and connect the nozzle. A fill begins but then stops abruptly: 0.2 kilograms. We try it again and the same thing happens.

“Hold on one second,” the technician says, as he kneels behind the pump and tinkers. Then, “try it again.”

We watch as the gauge climbs past a half, then one, then two kilograms. Four minutes later, our tank is full. We thank the technician and drive away, 250 miles distant from our next refueling trip.

*

Like all systems in beta, there are bound to be glitches with the hydrogen fuel cell car experiment. Some present tolerable inconveniences, and some disrupt the normal order of life to such an extent that some regret being an early adopter. One driver I spoke to on the phone, who lives in Morgan Hill, California, and works in a first-level trauma unit, described her experience with hydrogen-induced transportation insecurity as “emotional turmoil.”

Other drivers I’ve talked to seem unfazed and remain committed to the cause. “Electric cars have their own series of headaches,” Malone noted when we spoke. Such an attitude softens the frustration of a post-work fuel hunt, assuming your kids aren’t stranded on the playground because you’re in line for fuel.

For my family, the unpredictability of fuel availability has prompted us to drive my wife’s Subaru Forester on weekends or on short trips around town. We lament this dependence on oil’s hegemony. Occasionally I cancel trips or factor an extra hour into my commutes. I’ve started to be highly conscious of every mile I drive, regarding fuel as scarce. While scarcity is not the promise of hydrogen, it’s a fundamental truth of a future reliant on fossil fuels. As much as this experiment is fraught with disruption today, we can be certain that future disruptions wrought by a changing climate will be far more severe. What are we willing to tolerate by our own choice? Do we want to tolerate inconveniences now, before we are forced to endure future disruptions certain to be far worse? The truth is that none of us have the time to wait for some magical, faultless technology to emerge and solve our transportation-driven climate crisis.

I remind myself of hydrogen’s promises when the lines are long, when my car payment seems criminally high, and when the driver in front of me struggles to work the not-yet-perfected nozzle. Perhaps I need to remind myself a little more frequently.

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club