Make Colonizers Afraid Again

Indigenous activists are standing up to uranium

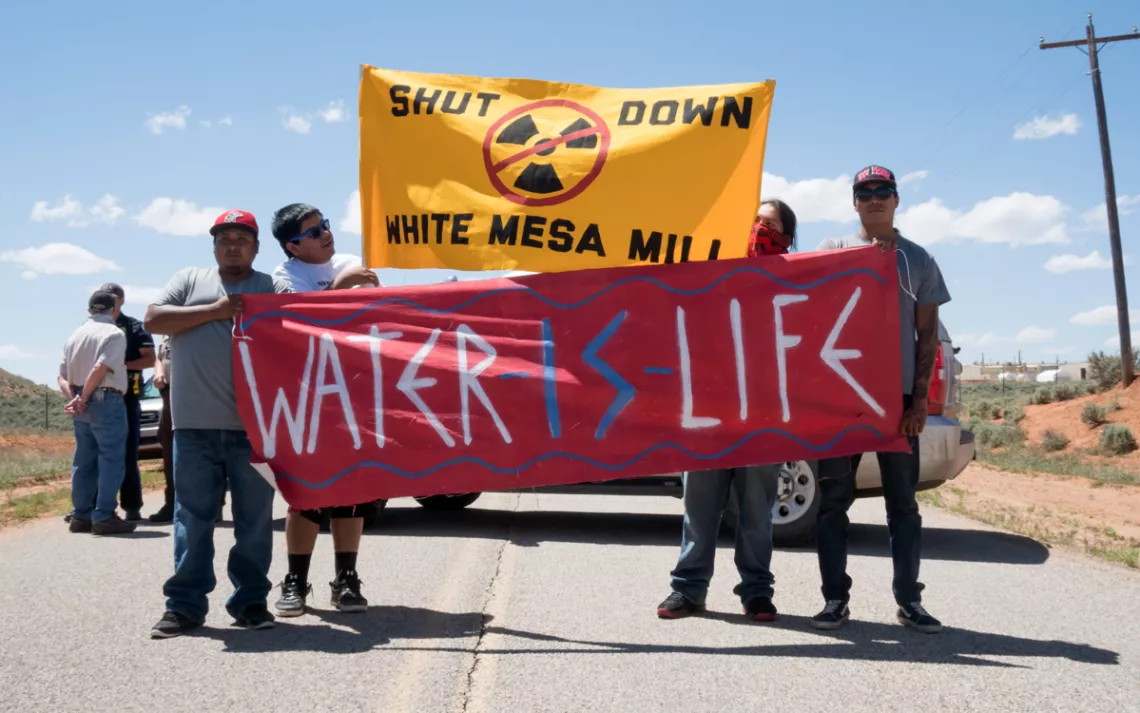

A May 13, 2017, protest by residents about the White Mesa Uranium Mill, just north of their reservation. | Photo by Corey Robinson

Klee Benally twisted his coffee mug in his hand, recounting a trip he took last year to Canyon Mine, a uranium operation six miles south of Grand Canyon National Park. A sticker kept flashing as he spun his cup. “Make colonizers afraid again,” it read.

“My attitude was confrontational,” said Benally—a punk musician, filmmaker, activist, and member of the Navajo Nation (or the Diné, the precolonial name for the people). “I was not interested in having a dialogue, especially in the context of a uranium mine desecrating a sacred site in the case of the Havasupai and a culturally significant one for Diné and Hopi.”

The site in question is Red Butte—Wii'i Gdwiisa to the Havasupai. It was severed from the Havasupai reservation as boundaries were drawn around Kaibab National Forest and Grand Canyon National Park, but Wii'i Gdwiisa remains part of the tribe’s traditional territory. In Havasupai cosmology, it is considered the earth’s umbilical cord.

The butte sits atop a complicated aquifer system that has never been fully mapped. It’s entirely possible that it is connected to springs and seeps throughout Grand Canyon National Park, including the iconic green-blue waterfalls of Havasu Canyon.

*

Two years ago, when Energy Fuels Resources (USA), a subsidiary of a Canadian uranium conglomerate with operations across six western U.S. states, announced plans to revive and expand Canyon Mine, a 1980s-era mining operation near the base of Red Butte, the Havasupai filed a lawsuit and sent leaders to Capitol Hill to protest. Mining the area around the butte could release uranium and heavy metals already present in the rocks into the aquifers, contaminating the water supply in unpredictable ways.

Benally focused on the route the uranium ore would take after it left Canyon Mine. Energy Fuels planned to send trucks through the Navajo Nation, which is still suffering from a legacy of cancer and kidney failure tied to previous uranium booms. Benally joined forces with Sarana Riggs and Leona Morgan, two other Diné activists. The trio began reaching out to residents along the trucking route and came up with a name for the project: Haul No!

One day last year, Benally and a group of activists carried a banner up to the gates of Canyon Mine to confront the workers. While they were there, they noticed something unusual. Large fans were misting water into the nearby forest. At first, Benally assumed it was for dust abatement. In a video, Benally can be seen asking the miners, “I presume that’s to keep the toxic material from blowing around, right?”

A worker responds, “There’s nothing here toxic. We’re not even mining uranium yet. [It’s for] evaporation.”

*

The protesters wouldn’t find out the full story until later. The miners had breached an aquifer as they were preparing for the mine’s reopening. The water flooding the mine shaft had levels of dissolved uranium that were three times levels that the EPA considered safe for drinking water. A filing that Energy Fuels had made with the Arizona Department of Environmental Quality (ADEQ) reported high levels of arsenic as well—29 times higher than EPA safety standards. The company’s response to the breach was to pump the water out of the shaft and disperse it with evaporation fans.

Meanwhile, state environmental permits that were meant to protect the area’s groundwater had expired. (The permits were later found, misfiled under the wrong county.) Energy Fuels’ Plan of Operations with the Forest Service—which hadn’t been updated since 1986—required that water be treated before leaving the mine, but tanker trucks were hauling some of the water from the breach over 300 miles to the White Mesa Mill in Utah.

In response, according to Alicyn Gitlin, Grand Canyon Program Coordinator for the Sierra Club, the Arizona Department of Environmental Quality changed the mine’s permit to allow for the use of evaporation fans. Months after Benally’s video helped expose the use of the fans, Gitlin said the latter regulatory agency allowed Energy Fuels to submit its own text to essentially rewrite their own permit.

Energy Fuels’ response to the aquifer breach disturbed Coleen Kaska, a member of the Havasupai Nation and an employee of the tribe’s wildlife department. In 2012, the Obama administration issued a 20-year ban on new uranium mining activity in the greater Grand Canyon area so more research could be done on the aquifers. Canyon Mine had suspended operations years ago, but it was exempt from the ban because it was an existing mine.

“As soon as people started learning about uranium mining near Grand Canyon National Park,” said Kaska, “a lot of tribes came and told us their own stories.” Native Americans living on reservations with a history of uranium development had a higher rate of birth defects than the population at large. To many, it was a clear legacy of the mines, and activists wanted to warn the Havasupai. “From the beginning,” said Kaska, “other tribes were supporting us in spirit, in language, in culture, in traditional spiritual feelings.”

“Our hang-out spots in high school were actually abandoned uranium mines,” recalled Sarana Riggs, who cofounded Haul No! with Benally. She grew up on the Navajo reservation near Tuba City and remembers that the local swimming holes were actually old open-pit mines. “We didn’t know it was a threat,” said Riggs, “and a lot of people still don’t know about the risks. There’s a lack of education.” Riggs’s grandfather worked in uranium mills and later died of stomach cancer.

There are roughly 500 abandoned uranium mines scattered across the Navajo Nation that have yet to see any significant clean-up efforts (clean-up typically involves capping mine tailings in place, treating contaminated groundwater, or relocating tailings to a less populated area).

Recent studies have suggested uranium sometimes bioaccumulates in mutton, a staple of the rural Navajo diet. And the ongoing Navajo Birth Cohort Study, which began investigating the impacts of uranium on the health of the Diné people in 2011, found in preliminary results that of 599 participants, 27 percent had high levels of uranium in their urine, including some infants, compared with 5 percent of the U.S. population as a whole.

Last year, Haul No! took Geiger counter readings near abandoned mines in Cameron, Arizona, a town on the Navajo Nation. At one mine, they watched the needle hit the peg on their counter even though they were standing well outside of a fenced-off mine area. The uncapped tailings from an earlier mining operation were washing through the barrier and toward the Little Colorado River. Houses sat less than a quarter mile away. “When we look at the impacts, we see a crisis,” said Benally, “but when we look at the action, it’s not being treated as such.”

*

If Canyon Mine reopens, up to 12 trucks per day, each carrying 30 tons of ore, could pass through Cameron and Tuba City on the way to White Mesa Mill. Trucks traveling to the mill have spilled radioactive waste at least twice in recent years. White Mesa, the last conventional uranium mill still operating in the U.S., is also owned by Energy Fuels. It’s situated above the aquifer that supplies the Ute Mountain Ute town of White Mesa with drinking water.

Groundwater contamination is also an ongoing worry, said Scott Clow, environmental programs director for the Ute Mountain Ute. While low global uranium prices have kept White Mesa Mill from operating at full capacity in recent years, three of the five impoundment cells surrounding the mill have single-layer plastic liners, rated to a 20-year lifespan. They were installed over 35 years ago.

There are groundwater monitoring wells in the area, but they are not directly under the impoundments, which makes it difficult to know the extent of possible breaches in the liners until contamination has already occurred. “To say these cells aren’t leaking is absurd,” said Clow. “The question is how much they’re leaking and what’s leaking.” (A spokesman for Energy Fuels told Sierra the company is in compliance with all state and federal environmental standards.)

*

The Ute Mountain Ute and Navajo were among the five tribes that participated in the Bears Ears Inter-Tribal Coalition and advocated for the creation of Bears Ears National Monument near White Mesa. With the urging of the coalition, the Obama administration set aside 1.35 million acres under the Antiquities Act in December 2016—including the land around the White Mesa Mill.

A year later, the Trump administration shrunk the boundaries of the monument by 85 percent after an extensive lobbying effort by Energy Fuels. The leader of the lobbying team hired by Energy Fuels was Andrew Wheeler, now head of the EPA.

The reductions to Bears Ears came as “a huge heartbreak,” said Regina Lopez-Whiteskunk, who represented the Ute Mountain Ute on the Bears Ears Coalition. Her son and his family live in White Mesa and drink bottled water largely because of concerns about the White Mesa Mill. “It makes you want to lose hope,” she said, “but the only thing we have to hang on to, no matter how you look at it, is hope. We have our children and our grandchildren and those yet to come to think about.”

In early 2018, Energy Fuels and Ur-Energy, another uranium mining outfit, petitioned the Trump administration to implement quotas that would require nuclear power plants to source a quarter of their uranium from mines within the United States. Roughly 20 percent of electricity in the U.S. comes from nuclear generating stations. According to Energy Fuels, only 4 percent of the uranium used in reactors is mined domestically—the rest comes mostly from Kazakhstan, Russia, Canada, and Australia.

If Commerce Secretary Wilbur Ross grants Energy Fuels’ request and implements quotas, it will likely lead to a surge of uranium mining on American public lands. It could also cause the cost of nuclear power to skyrocket. The Nuclear Energy Institute (NEI) estimates Energy Fuels’ proposal would cost producers $500 to $800 million dollars per year—putting some plants at risk for premature closure. (Energy Fuels disputes NEI’s findings.)

*

In early October, Havasupai leaders hosted an inter-tribal gathering in the national forest between Red Butte and Canyon Mine. I drove from White Mesa Mill to the gathering along the proposed haul route. There had been heavy rains the night before, and when I stopped at an abandoned uranium mine just off the highway in Cameron, I saw where the rain had dug gullies in tailings piles and swept them downhill.

I drove on into Grand Canyon National Park and arrived at the outdoor gathering that afternoon. A Hopi reggae band was playing their take on a Bobby McFerrin tune: “Don’t Worry, Be Hopi.” Diné activists representing Haul No! and members of Diné No Nukes spoke to the crowd while volunteers from Prescott College served meals. Lopez-Whiteskunk had told me that a unified coalition of Havasupai, Hopi, Diné, and Ute Mountain Ute people “could be the next effort” to resist Energy Fuels’ activities—the Bears Ears Inter-Tribal Coalition had already shown one way that local tribes could work together.

Havasupai leaders continue to travel to Washington, D.C., to speak out against Canyon Mine. The Hopi, Zuni, Ute Mountain Ute, Diné, and Ute Indian tribes have joined forces to sue the Trump administration over the cuts to Bears Ears. Meanwhile, Haul No! recently led a series of Indigenous-rooted trainings for participating in peaceful direct actions in communities between Flagstaff and White Mesa. If Energy Fuels’ petition for quotas is granted, and uranium extraction begins at Canyon Mine, Benally said, Haul No! will be ready.

“When you look at the ongoing impacts of past uranium mining and the threats of renewed mining and milling, this is a question of our future,” Benally said. “This deadly toxic legacy is, to me, tantamount to the slow genocide of our people. We have so many deaths, we have so much cancer, and almost nothing being done about it.”

“What will the response be from activists if hauling begins from Canyon Mine?” I asked.

“We’ll shut it down,” he replied.

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club