Senate Passes Epic Public Lands Bill

The Great American Outdoors Act funds the acquisition and maintenance of parks nationwide

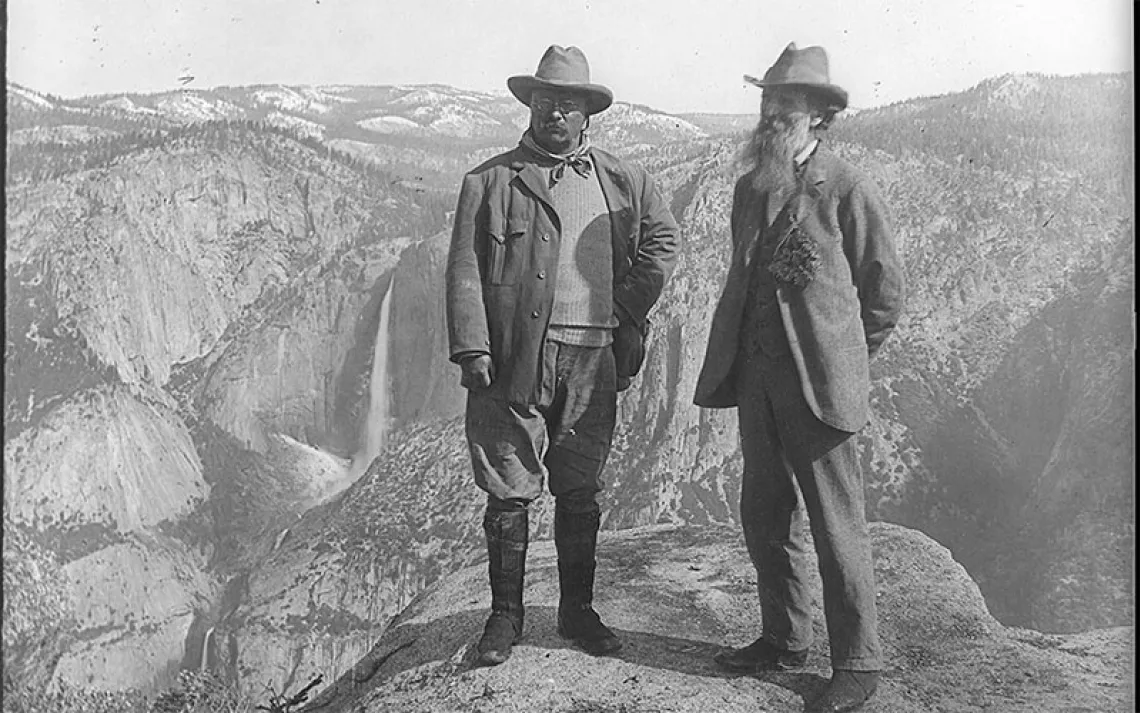

The National Park Service maintenance backlog includes utilities like this leaky water line in Grand Canyon National Park. | Photo by AP Photo/National Park Service

On Wednesday, in a rare show of bipartisanship, the Senate passed the Great American Outdoors Act by 73-25.

It’s a significant victory in a legislative session that has been primarily focused on responding to the COVID-19 pandemic and the resulting economic recession. While most other legislation has been in limbo, the Great American Outdoors Act is one of the few bills to make it to a vote.

The bill makes two important contributions toward securing a sustainable future for public lands and waterways: It permanently allocates $900 million annually to the Land and Water Conservation Fund (LWCF) and directs $9.5 billion to fund the National Park Service’s substantial maintenance backlog. The House is expected to pass it in early July, and President Trump has said that he will sign it into law.

“People across the country need healthier, safer, and better access to public lands, parks, and outdoor spaces where we can build community and care for ourselves physically and emotionally,” said Jamie Williams, president of the Wilderness Society, in a statement. “Today’s Senate passage of the Great American Outdoors Act gets us a step closer to Congress keeping a promise to the people it serves to invest in the natural, cultural, and recreational resources that anchor our communities.”

The LWCF was created in 1964 to purchase and protect recreation areas across the country. It was permanently authorized last year but has only been funded sporadically over the years. “Even though it’s been really popular and bipartisan, it’s taken us forever to get it over the finish line,” says Athan Manuel, director of the Sierra Club’s Lands Protection Program, referring to the 56-year gap between the creation of the program and its permanent endowment.

Funded by royalties from the oil and gas industry, the LWCF has been used to purchase protected areas in the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem and to expand Acadia National Park. It preserves working forests and ranches, historical sites, and hunting and fishing access points. Additionally, in partnership with state and local governments, it funds city parks and trails.

In a 2018 poll conducted on behalf of the California League of Conservation Voters, two-thirds of respondents supported long-term funding of LWCF. One reason it could be so popular is that it is not taxpayer-funded. “It’s not the most glamorous program in the world—it’s not the Clean Air Act or the Clean Water Act or the Wilderness Act—but it’s significant,” Manuel says.

The bill’s second notable accomplishment is establishing the National Parks and Public Land Legacy Restoration Fund, which would put a $9.5 billion dent in the National Park Service’s $11.92 billion maintenance backlog over the course of five years. It’s funded by federal revenue from energy development (including oil and gas, coal, and renewables) on federal lands and waters.

The national parks have been chronically underfunded for decades, even as visitation to some parks has increased by as much as 60 percent. According to Kathy Kupper, a public affairs specialist at the National Park Service, there are $6.15 billion of repairs needed on roads, bridges, and parking areas as well as $5.77 billion in repairs on other infrastructure including buildings, utilities, campgrounds, and trails. Since the fund would not cover the entire maintenance backlog, Kupper says, the National Park Service will create a list of priority projects for each park.

The bill received bipartisan support thanks to a handful of Republican senators—including the bill’s sponsor, Cory Gardner (R-Colo.)—who face tough reelection races in November. Manuel says senators who “ran as moderates and governed as Trumpers” are hoping that the legislation will make them appear more moderate. Regardless of why the bill was able to make it through a notoriously partisan Congress, it’s good news for all Americans, who continue to support public lands regardless of political affiliation.

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club