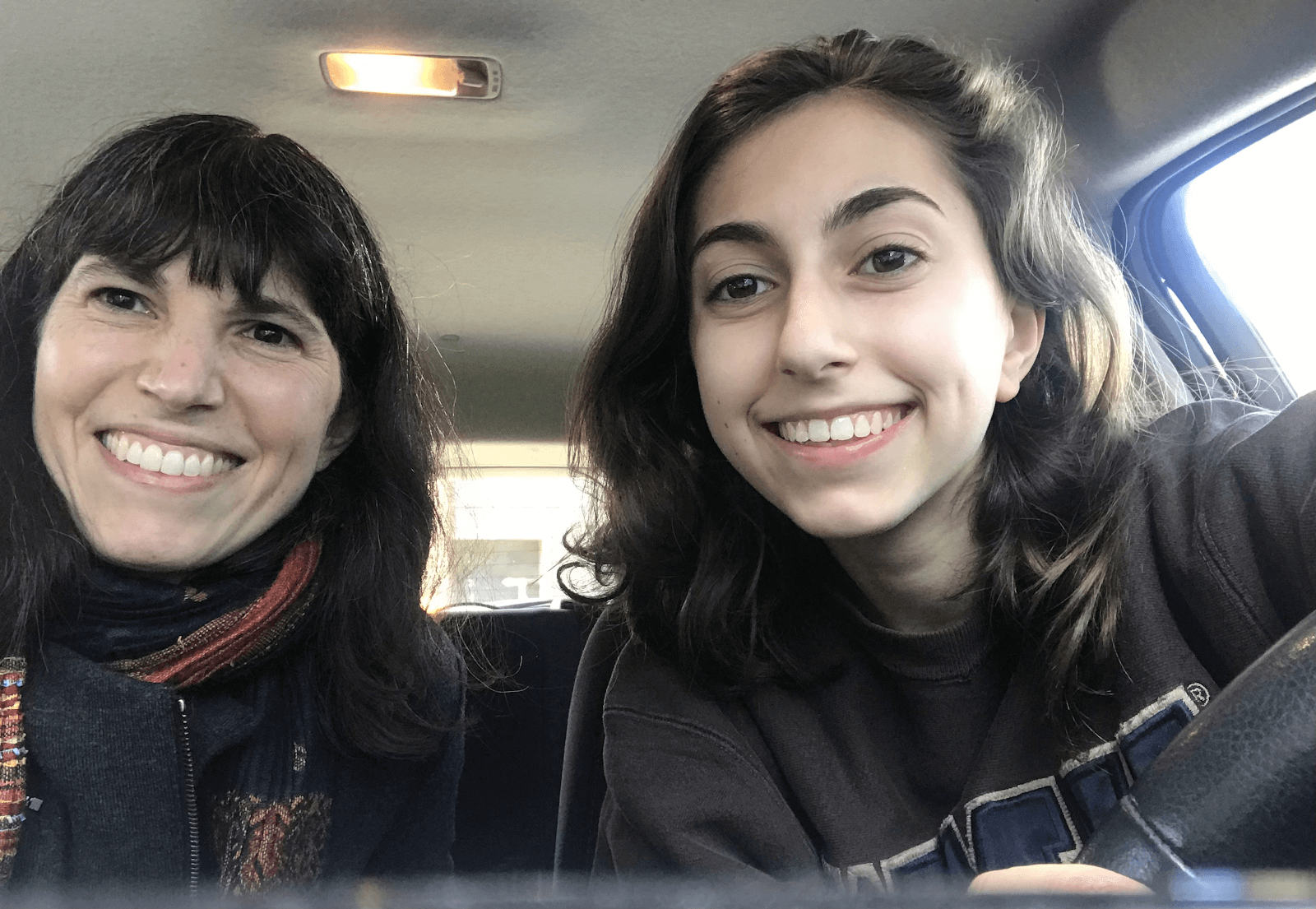

I’ve advocated for clean transportation policy for more than a decade, and I’ve always had a fire in my belly for this work, but recently, the topic has been feeling even more personal. My daughter Farah turned 16 in February and took the test to get her learner’s permit. It included outdated questions like the one about the tailpipe on her car (the all-electric Nissan LEAF in which she’s been learning to drive has no tailpipe). The test also included questions that seemed irrelevant (like the one that asked the exact amount of the fine for drag racing, which our other daughter Dori thought was in reference to RuPaul).

Not surprisingly for people of their generation, some of Farah’s friends aren’t particularly interested in driving, in part because we live in a city with good public transit and robust pedestrian and biking infrastructure. But Farah was excited to get behind the wheel, and she passed the permit test. Watch out, neighbors in Cambridge, Massachusetts! (Actually, she has been doing really well in her practice sessions.)

This rite of passage for my daughter has gotten me thinking about the past, present, and future of transportation in the United States. When Farah was born in 2005, we had no electric vehicles (EVs) on the road, only gas guzzlers that contributed not only to climate change but also to the asthma and other respiratory conditions that she and millions of Americans endure. Public transit and active mobility choices like biking and walking were accessible to some, like us, but not to many others. Back then, the electricity sector was the largest source of greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions in the US.

Today, transportation is the largest source of GHG emissions, with bigger SUVs and pickup trucks making up the majority of vehicles purchased in this country. Revenue sources for public transit, already in trouble before the COVID-19 pandemic, have cratered over the past year. Pollution from ports and logistics warehouses has increased dramatically, making life more dangerous for the mostly Black and brown communities in the so-called “diesel death zones” where these dirty facilities are sited.

There are some areas of hope and progress. Currently, there are nearly 2 million electric cars in operation in the US, and people are loving how smooth, quiet, and clean these vehicles are. EVs are significantly lower in emissions than oil-powered vehicles, even factoring in the emissions from the electricity used to charge them, and they are only getting cleaner over time as we shift to renewable sources of power. California has committed to fully electrify its transit buses as well as its truck fleet, and other states may soon follow. Ride-hailing companies like Uber and Lyft have pledged to fully electrify their fleets in the US by 2030. Utility companies and others have committed billions of dollars to install charging infrastructure for cars, trucks, and buses. Public interest in biking and walking has blossomed during the pandemic, resulting in a surge of new policies promoting “safe and open streets.”

What should transportation look like 16 years from now, in the year 2037? My vision -- developed with help from several colleagues -- is for a future in which:

-

No matter their zip code, race, income level, or age, everyone has access to clean and safe transportation options, including public transit, electric vehicles (and the infrastructure to charge them), ride-hailing/sharing, rail, and micro-mobility (walking, biking, scooters, etc.).

-

All new -- and most old -- cars, trucks, and buses run on batteries charged by clean electricity (or other sources of renewable power).

-

Residents living in communities where ports, logistics hubs, airports, and freight systems operate breathe clean air every day.

-

Transportation policies encourage infill development and working from home, discourage sprawl and vehicle miles traveled, and allow people to access jobs, housing, education, nature, and community.

-

Government and corporate transportation policies are developed in the public interest in partnership and consultation with the communities most impacted by transportation challenges.

-

Policymakers understand that systemic racism in our nation has greatly influenced transportation policies, and they develop new transportation policies with an intersectional lens that considers equitable housing, health, jobs, policing, etc.

-

Transportation workers in the US -- including those who work in manufacturing, public transit, trucking, rail, ride-hailing, infrastructure, delivery, and logistics -- have access to increasing numbers of local, family-sustaining, union jobs.

How will we get there? It won’t be easy, but last week we took a massive leap forward. President Biden’s proposed jobs and infrastructure plan includes transformational investments in clean transportation. This includes a $174 billion investment to “win the EV market.”

His plan will enable automakers and their supply chains to retool factories to compete globally and support American workers in making batteries and EVs. It will give consumers incentives to buy American-made EVs, and ensure that these vehicles are affordable. It will fund a network of 500,000 EV chargers by 2030, while promoting strong labor and training standards. His plan also will replace 50,000 diesel transit vehicles and electrify at least 20 percent of our yellow school bus fleet. Finally, it will lead to the electrification of the federal fleet, including hundreds of thousands of US Postal Service vehicles (a plan that would need to overcome challenges I and others have raised recently on NPR, Atlas EV Hub video podcast, in Congress, etc.).

Biden’s proposal also went way beyond vehicle electrification, including:

-

Investing $85 billion to modernize existing public transit and help agencies expand their systems to meet rider demand.

-

Investing $17 billion in inland waterways, coastal ports, land ports of entry, and ferries, all of which are essential to moving our nation’s freight. This includes a Healthy Ports program to mitigate the cumulative impacts of air pollution on neighborhoods near ports, which are often communities of color.

-

Redressing historic inequities and building the transportation infrastructure of the future, including a $20 billion new program that will reconnect neighborhoods cut off by racist “urban renewal” projects.

-

Investing $80 billion to address Amtrak’s repair backlog.

And that was just surface and marine transportation. The proposal also included major investments in bridges, the airline industry, broadband, drinking water, the electric grid, public parks, agriculture, and much more. According to a Sierra Club analysis, we can and must go even bigger and further to meet the enormous challenges of our time on climate, jobs, health, and social inequities. The THRIVE Act, soon to be introduced in Congress, spells out some important ways to do that.

It is now up to Congress to turn this vision into strong law and policy, and implement it in a way that truly transforms our society. If it does what we need it to do -- create millions of jobs, protect our health, slash planet-warming emissions, and provide us safe, affordable, and clean ways to move -- then this new plan will bring personal, long-last benefits to all of us --and future generations too.