On Scaling a Historic Fire Tower in Washington's North Cascades

The allure and romance of remote, one-room mountaintop cabins

Washington's Mt. Pilchuck, home to one of the remaining 2,000 fire towers scattered across the United States. | Photo by Mitch Pittman/Tandem Stills + Motion

The weathered white cabin clung to the top of a jumble of boulders, anchored by cables as thick as my wrists.

"Do I look like a mountain goat?" my best friend, Leigh, asked with raised eyebrows. "No thank you."

We had just huffed up more than 2,000 feet of mountain, and this was the final push to the triangular summit of Washington's Mt. Pilchuck. There was no way I wasn't going up there. So Leigh's younger sister, Sarah, and I scaled the giant rocks to arrive at the cabin, a fire lookout built in 1918, during an era when the only reliable way to spot wildfires before they billowed out of control was to staff remote one-room cabins high on mountaintops.

The forests of the United States—and especially the Mountain West—are dotted with these old, spartan fire towers. At one point, there were as many as 8,000, a lot of them built as Depression-era Civilian Conservation Corps projects. Over the years, technology has rendered the towers' fire-watching function obsolete, and few remain staffed. (Though in a handful of recent cases, lookout employees have proved to be more effective than drones, satellites, and infrared cameras.) Today, only about 2,000 towers are still standing. Some are accessible via day hikes, and some are rentable overnight.

Since my first fire-tower hike up Mt. Pilchuck over a decade ago, I've ascended around a dozen others throughout Washington State's Cascades, dangling my legs from their wraparound balconies and drinking in the view while eating my trail lunch. Sometimes their windows are boarded up. Other times they have simple cots and the odd remnant of fire-spotting equipment, like miniature mountaintop museums.

Fire lookouts were lonely posts, but there was romance in that solitude: To be cloistered high in the mountains with little human contact for months held a certain appeal. That idea took hold of beat poet Jack Kerouac, who staffed a tower atop the North Cascades' Desolation Peak for 63 days in the summer of 1956. Perhaps unsurprisingly, he proved to be a poor lookout, frequently turning off his radio to write. His experience in the tower inspired material in two future novels, The Dharma Bums and Desolation Angels. Likewise, Edward Abbey's fire-lookout experiences made cameos in Desert Solitaire and Black Sun, and Gary Snyder wrote about his time as a lookout in the North Cascades for Sierra.

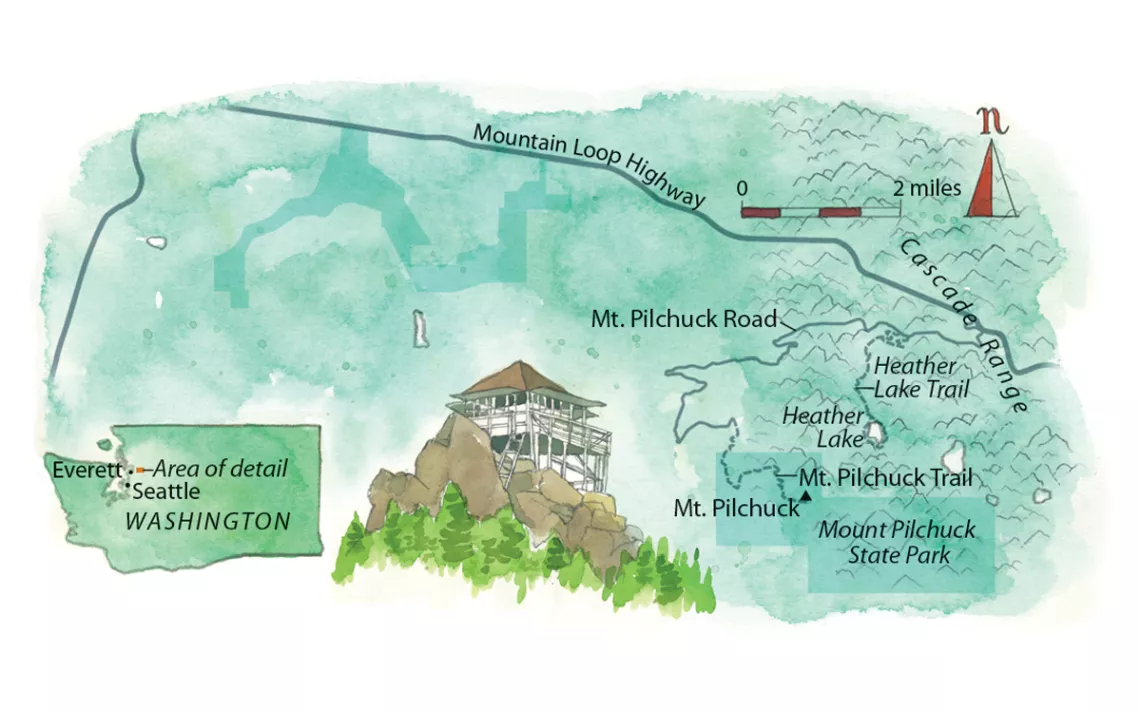

Map by Steve Stankiewicz

"It was miles and miles of unbelievable mountains grooking on all horizons in the wild broken clouds, Mt. Olympus and Mt. Baker, a giant orange sash in the gloom over the Pacific-ward skies that led I knew toward the Hokkaido Siberian desolations of the world," Kerouac wrote in The Dharma Bums.

I've been hooked ever since I first climbed Pilchuck's ladder and stepped inside the tower. All told, the adventure requires a relatively short hike, about 5.5 miles round trip, but the trail ascends some of the Pacific Northwest's best scenery. First, it moves through old-growth forests of cedar and fir where giant slugs munch mushrooms and ferns could hide a mountain lion. Above the trees, the trail climbs past vast fields of lichen-splotched boulders where pikas squeak and scurry.

Reaching the summit on that last trip, Sarah and I found unobstructed views of the Cascade Range, blue ripples that run the length of the eastern horizon, with the occasional glaciated peaks of stratovolcanoes—Mt. Baker and Mt. Rainier—rising like white clouds above a sea. The more distant Olympic Mountains to the west seemed to hover in a gray haze. Sarah comforted her heights-wary self by quietly humming words of encouragement. I'm not at all surprised views like this filled Kerouac with made-up words. There's something about being surrounded by mountain peaks that makes me want to fling the existing lexicon into the void.

The summit of Mt. Pilchuck isn't an uncrowded place—thanks to its proximity to Seattle and its knockout views—and the longer we took in the panorama, the more people we shared it with. Still, the vista never fails to strike a Kerouacian chord. After all, the Mt. Pilchuck lookout hearkens back to a simpler time, one when cellphones didn't constantly buzz with messages and Facebook notifications.

When I visit these lookouts, I always hope that their dizzying perches will dislodge some of my own beat poetry. I imagine myself holing up at a tower for the short duration of a Northwest summer with nothing to do but stare into the clouds and search the skies for strikes of lightning.

Find an exciting fire-tower hike near you: sc.org/fire-towers.

Take a Sierra Club trip to the Pacific Northwest. For details, see sc.org/adventure-travel.

This article appeared in the January/February 2020 edition with the headline "Historic Heights."

WHERE

Mt. Pilchuck, Mount Pilchuck State Park, Washington

GETTING THERE

Take the Mountain Loop Highway to Mt. Pilchuck Road. Follow it for 6.8 miles to the trailhead parking lot.

WHEN TO VISIT

The trail is accessible all year, but June through September is the best time to go. (Otherwise, be prepared for snow on the trail.)

PERMITS

A Northwest Forest Pass is required to park at the trailhead.

MUST-SEE

The Mountain Loop Highway wends through impressive North Cascades scenery and offers access to a number of worthwhile trails leading to Lake 22, Heather Lake, the Big Four Ice Caves, and other sites.

PRO TIPS

Extreme weather can encase Mt. Pilchuck in fog, rain, or snow. If snow is a possibility, bring poles and traction devices, and be prepared for route-finding in case the trail becomes obscured. The trail is very popular, so plan your trip for a weekday if possible.

ADDITIONAL READING

Fire Season: Field Notes From a Wilderness Lookout (Ecco, 2011) by Philip Connors

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club