Hope Springs Eternal

A reporter’s notebook from the Global Climate Action Summit

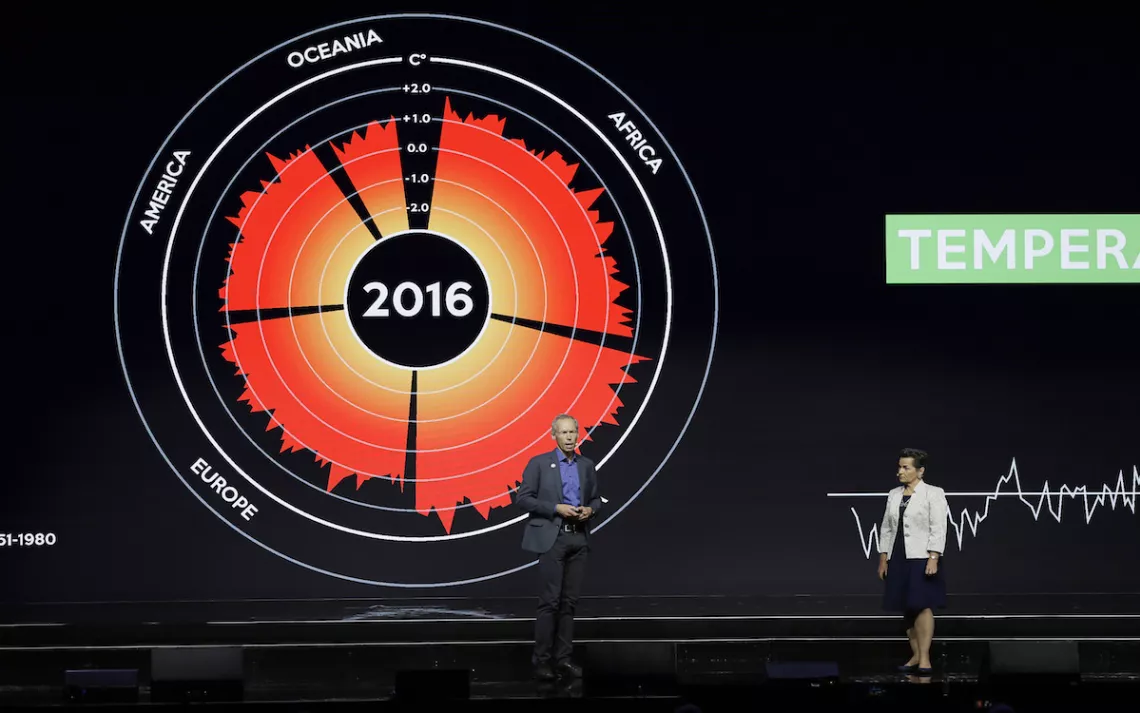

Johan Rockstrom, left, the executive director of the Stockholm Resilience Center, and Christiana Figueres, founding partner, Global Optimism and Convenor, Mission 2020, give a presentation during the opening plenary of the Global Action Climate Summit on September 13, 2018, in San Francisco. | AP Photo/Eric Risberg

At the Global Climate Action Summit in San Francisco this week, the optimism was as brilliant and as hard as a diamond, a thing formed by all the pressure in the world.

The summit had been organized by California governor Jerry Brown and philanthropist Michael Bloomberg to demonstrate to the world that a great many elected officials and business leaders in the United States remain committed to the Paris climate agreement, even as Donald Trump steamrolls one U.S. environmental protection after another. The 4,000-plus delegates who converged on San Francisco had clearly gotten the message that cynicism and nihilism weren’t invited to the glittering gathering. At the official plenaries, at the hundreds of affiliate events, and in every one of the scores of press releases filling up reporters’ inboxes, the vibe was doggedly upbeat.

Christiana Figueres, the Costa Rican diplomat who ushered the UN-brokered Paris Agreement to success, captured the zeitgeist of the summit during a Wednesday gathering of mayors at San Francisco City Hall. “I call myself a stubborn optimist,” she said. “I have learned that it’s not helpful, in the pursuit of an achievement, to be pessimistic. What’s the point? You have to start with optimism; otherwise you’re not going to achieve anything.”

“We have to stay optimistic. We have to stay optimistic,” Inia Seruiratu, the minister for agriculture and rural and marine development for Fiji, said during a Friday panel. “The momentum is picking up, and I think it’s all about partnerships.”

Todd Stern, the flinty former U.S. diplomat who guided American climate change foreign policy during the Obama administration, was equally determined, despite the climate-wrecking industry stalwart living in the White House. “The U.S. is not there at the political level, so that is concerning,” Stern told me. “There is an effort by some countries to kind of move backwards from some of the important advances and steps forward in Paris. But there is plenty of time to get that right. It is in my nature, and this was true for the seven and a half years that I was there [heading U.S. climate diplomacy] that I was rarely optimistic and I was rarely pessimistic. I don’t really get pessimistic.… It’s not that I think everything is going well. It’s that if I see a challenge, I mostly get to thinking very quickly about how do we try to deal with it. I don’t wallow.”

But in private, off-the-record conversations, many confessed that the situation is grim. Already we’ve hit a 1.1˚C average global temperature rise, and the effects on the climate—record-breaking heat waves, unprecedented storms, a longer wildfire season—are appearing sooner than many climatologists would have predicted only a decade ago. The national commitments made during the first round of the Paris process have us on track for a 3.2˚C global temperature increase (while no one wants to publicly imagine what such a scenario would look like, it might look like alligators on the shores of Hudson Bay). Today there are some 1.4 billion people without reliable access to electricity, and by mid-century we may have another 2.5 billion human mouths to feed. The oceans may finally be reaching the limits of how much heat and CO2 they can safely absorb. “We’ve clearly already passed some tipping points,” one state-level environmental regulator told me.

To acknowledge the facts as they are is not to say that all the public hopefulness is a charade, or some kind of magical thinking. Combine outward optimism and inward gloom and what you get is live-wire urgency—a sense that the clock really is nearing midnight. “There is not a huge window of time,” Jane Goodall warned during an appearance on Friday. “We need to act now, all of us.” Anne Hidalgo, the mayor of Paris, declared, “It’s time. It’s time to act now.”

If the hour truly is late, then there is no alternative to optimism. We have no choice but to remain hopeful. The difference between a global average temperature increase of 1.5˚C and 2.5˚ or 3.5˚ is all the difference in the world—literally, the difference of what kind of planet we hope to live on.

• • •

Photo by Jason Mark

More than a few of the delegates at the summit expressed confusion about what, exactly, the point was. “Discombobulated,” “strange,” and “improvised,” were among the adjectives I heard used to describe the gathering. The Global Climate Action Summit was a unicorn: a high-level convening without the world-historical force of formal UN negotiations (and none of the hurried scurrying between backrooms), but something with more political oomph and star power than most other gatherings of climate change insiders.

There was Harrison Ford looking and sounding like an Old Testament prophet, begging the audience not to “forget nature” and declaring, “If we don’t protect nature, we can’t protect ourselves.” And there was Al Gore, the elder statesman of the climate action movement, sounding like a Baptist preacher as he roared about “fire tornadoes” and saying that “each night on television is like hiking through the Book of Revelations.” Dave Matthews played a couple of songs, and a Republican mayor from Indiana insisted, “Regardless of Washington, the people of our country will keep the promise made in Paris.”

And that was just the action on the main stage. Throughout the week, San Francisco and neighboring cities hosted more than 300 affiliate events. In the plush confines of the Four Seasons, the Chinese government organized a kind of shadow summit featuring some of the most fearsomely nerdy and smart climate-solvers on the planet. A group of photographers and artists put together a 50,000-square-foot exhibit called Coal + Ice, while a Santa Fe artist named Don Kennell erected a 35-foot-tall polar bear on the city’s main waterfront plaza. On Wednesday afternoon, Grace Cathedral held a “multifaith service of wonderment and commitment” that included Christians, Muslims, Buddhists, Jews, Hindus—plus six stilt walkers garlanded with vines, feathers, and fern fronds, like ecumenical Ents.

PHOTO COURTESY OF SHELBY THORNER

But it wasn’t all pageantry and gabfest. Real work got done. “This summit is about saying, ‘We need to make lemonade out of lemons, because the federal government is MIA,’” one of the summit organizers told me. “Paris is a bottom-up model that is stuck at the national level, even as the real action is coming from the ground. We’re going to step into the gap and change how we think about climate action.”

In that sense, at least, the summit was successful. Perhaps the biggest news of the week came from the U.S. mayors and governors who came to make significant announcements about their efforts to cut greenhouse gas emissions. More than two dozen cities, states, and businesses—including big names like Los Angeles—committed to taking their transportation fleets to zero-emission by 2030. Connecticut, Maryland, and New York announced plans to begin regulating super-pollutants like HFC in 2019. The 17 states that are part of the U.S. Climate Alliance said they would use at least $1.4 billion from the Volkswagen “Dieselgate” settlement to drive down automobile emissions. New York City mayor Bill deBlasio made something of a splash on Thursday when he announced that $4 billion of the city’s pension fund would be invested in renewable energy companies. According to a report released on the eve of the summit by Bloomberg Philanthropies, the United States is about halfway to its Paris Agreement target of cutting emissions at least 26 percent below 2005 levels by 2025—thanks mostly to state and local actions. (Disclosure: Bloomberg Philanthropies is a significant donor to the Sierra Club.)

The commitments from the business sector were less impressive. “Less impressive” may be overly generous; for the most part, the corporate commitments were a nothing burger. Yes, Mahindra & Mahindra, a $20 billion Indian conglomerate that manufacturers utility vehicles, announced it would be carbon neutral by 2040. Unilever announced it would take steps to stop deforestation in the Sabah region of Malaysia, and electric vehicle infrastructure company ChargePoint said it would install 3.5 million charging stations by 2025. This is all good stuff, and you’d have to have a real eco-scrooge to dismiss such promises.

Yet many announcements were small-bore. Take Levi Strauss. The clothing company says it is committed to a 90 percent reduction in GHG emissions from its “owned and operated facilities”—which is great, until you stop and consider that most of its production is done by subcontractors. “We need to go beyond commitments,” an executive at one renewable energy company told me. “At this point, what we need is follow-through.”

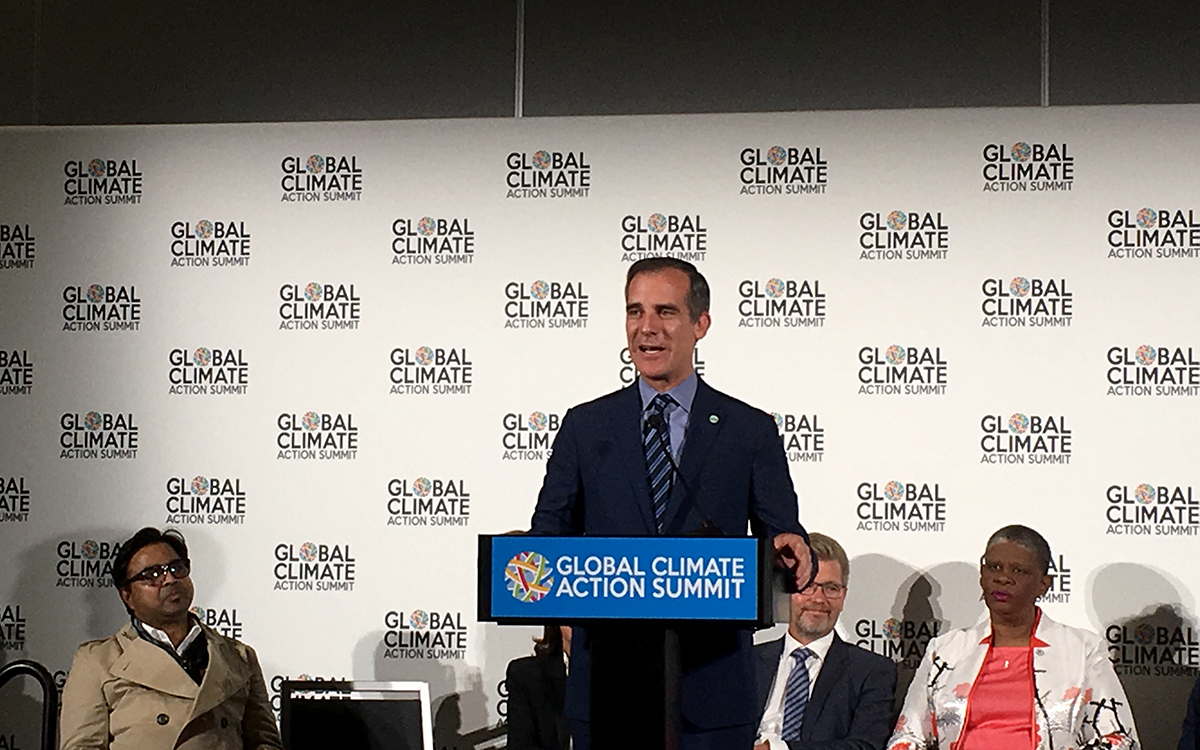

The gap between the announced commitments and the scale of action everyone knows we need made for a kind of cognitive dissonance. When measured against the status quo, the ambition of policymakers, business leaders, and NGO advocates is awesome. When measured against the implacable physics of the planet, the ambition is frighteningly insufficient. Such disparity prompted one climate leader, Mayor Eric Garcetti of Los Angeles, to make a neologism: anxcited, full of anxiety and excitement.

“It’s like every day, this feeling of ‘anxcitement,’” Garcetti told me when I asked him about his mood. “Wow, we are finally there and we can do this. And it’s getting worse simultaneously. It’s a race. Will things get so bad, a couple of speakers talked about it, an irreversible tipping point and a ‘hothouse Earth’ that has a self-actualizing cycle of getting hotter and hotter? That’s very, very scary. And it’s absolutely possible. But if you look at exponential growth on renewables and recycling and electric vehicles—and we’re experiencing exponential growth—then we can stop this. Humans are very good at one thing: We’re very good at surviving.”

PHOTO BY JASON MARK

• • •

One of the stranger things about the past week was the fact that the biggest, most ambitious commitment to come out of the Global Climate Action Summit got so little attention. As David Roberts of Vox explained it, the announcement was “so out of left field and yet so profound in its implications that few in the media, or even in California, seem to have fully absorbed it yet.” That was Governor Jerry Brown’s executive order to make California, the world’s fifth-largest economy, totally carbon neutral by 2045, five years ahead of the Paris Agreement deadline.

I think it’s fair to say that Governor Brown wouldn’t have taken that leap—or at least not that exact leap—had it not been for the protests in the streets.

For the last several months, Brown has been taking fire from grassroots environmentalists calling on him to place a moratorium on new oil and gas drilling in California. The “Brown’s Last Chance” campaign, as activists call it, snatched some headlines last Saturday, when thousands of people marched down San Francisco’s Market Street in a welcome-challenge to the summit. The protests continued throughout the week, with a large rally early Monday morning outside a meeting of the governor’s Climate and Forest Task Force and then a traffic-stopping march on Thursday. Criticism of Brown’s leadership even made it onto the main stage. The summit started with a performance and acknowledgment of Native American ancestral land by an Ohlone woman named Kanyon Sayers-Roods, who made her allegiances quite clear. “I am a sky protector,” she said, in an obvious echo of the Indigenous protesters in the streets. She then closed with these lines: “I’m going to say it. Don’t support carbon-trading; keep fossil fuels in the ground.”

The criticism appears to have gotten under the governor’s skin. At a Thursday press conference, he was visibly annoyed by reporters’ repeated questions about the demands from grassroots greens, Native Americans, and other protesters. “I get hassled by experts on all sides,” Brown said. “For every position there is a counter position, and for every counter position there is a counter-counter position. California has the most comprehensive, integrated oil-reduction plan in America. And I say that as an understatement.”

Brown’s critics were reluctant to give the governor much praise for the executive order. But it appears they got some of what they wanted—a sunsetting of the California oil and gas industry—though not on a timeline they would like. After all, it would be all but impossible for California to reach carbon neutrality and still be a major fossil fuel producer.

“It’s a nod and a middle finger at the same time,” Annie Leonard, the executive director of Greenpeace USA, told me.

• • •

PHOTO BY JASON MARK

Among many of those wearing official delegate badges, there was a certain level of summit fatigue, a sense that yet another convening is unlikely to get us much closer to stopping and then decreasing greenhouse gas emissions and deforestation. “It’s like all they know how to do is a conference,” one environmentalist, a veteran of several rounds of UN negotiations, wrote to me in email. At a meeting of national ministers hosted by the Dutch Consulate, I heard Paul Polman, the CEO of Unilever, complain, “The direction we need to go is clear, but we spend too much time educating ourselves. It’s not enough anymore.” From that lofty perch on the 31stfloor of a steel and glass office tower, I could see an oil tanker heading toward the Golden Gate.

Polman’s weariness is understandable. After all, when it comes to climate action, tomorrow seems to keep getting pushed off into the future. Just think about all the rhetoric during the eve of the ill-fated Copenhagen Summit, when heads of state and righteous NGO-istas warned we had until 2015—2020 at the latest—to take drastic action to avoid the worst consequences of climate dislocation. Those consequences are starting to make themselves felt, 2020 is almost upon us, and everyone agrees “the time for action is now.” Yet the actions still appear incommensurate with the problem.

Perhaps that’s the nature of big, disruptive social changes. As I heard Mayor Garcetti say on a couple of occasions, it’s essential that “our reach exceed our grasp.” That is, to make progress we must to aspire to something that is currently unachievable, something we can barely even imagine.

The massive challenge of making a global transition away from fossil fuels and unsustainable resource consumption is sometimes compared to a moonshot—a big, bold endeavor. At a reception celebrating the accomplishments of the fossil fuel divestment movement ($6.24 trillion and counting), a longtime climate change policy wonk and summit gadfly, Tom Athanasiou, reminded me that, on the Apollo 13 lunar mission, the astronauts had to execute what’s called a “gravitational slingshot” around the moon to get their busted spacecraft back to Earth. At the risk of stretching a metaphor beyond its breaking point, we are in just such a “slingshot moment,” Athanasiou said. We need to increase velocity fast to push civilization into a whole new direction.

It’s difficult to see how to do that; our grasp exceeds our reach. But the big, ambitious, and, yes, sloppy Global Climate Action Summit did assist in the task. It helped to create just a little bit more momentum, a little bit more force, to take us in a new and necessary trajectory.

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club