Smoke Gets in Your Eyes … and Mouth and Lungs Too

Wildfire smoke presents a real threat to public health

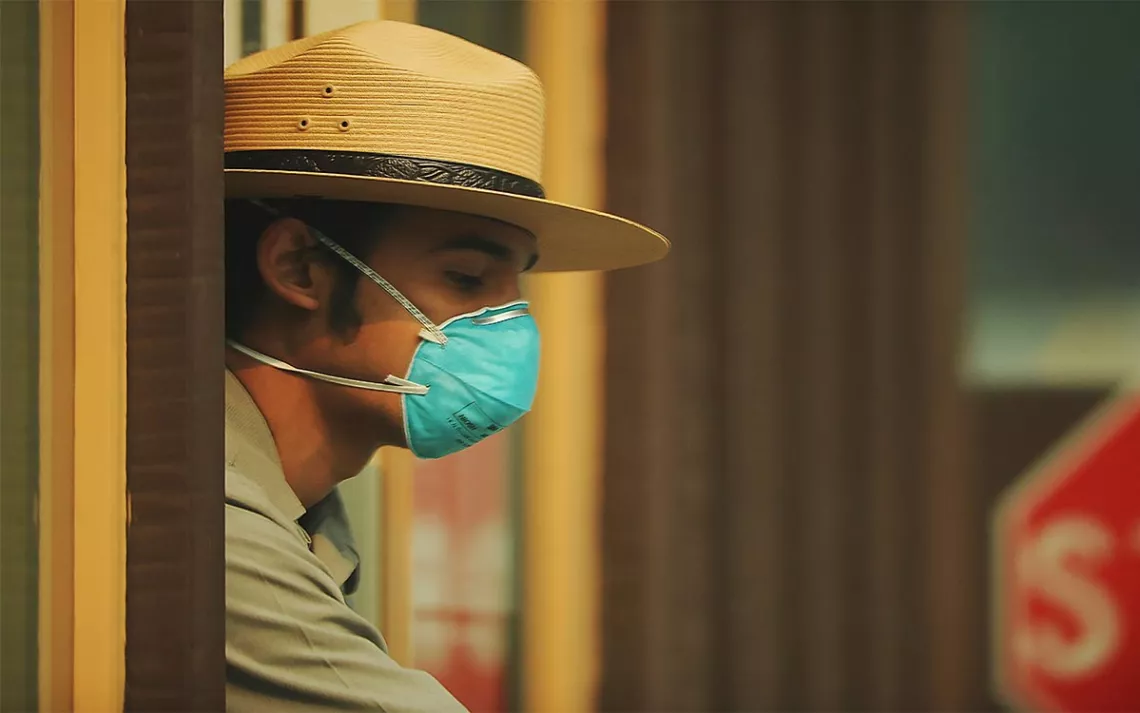

Victor Woodley wears a mask due to smoke while taking entrance fees at the south entrance to Yosemite National Park in July 2018. | Photo by Eric Paul Zamora/The Fresno Bee via AP

Wildfires are burning in California. There are now at least 18 major fires tearing across the Golden State, leaving a trail of death and destruction. The Carr fire around the city of Redding has destroyed an estimated 1,000 homes and killed at least six people. The Ferguson fire prompted the closure of Yosemite National Park on July 23, and visitors aren’t expected to be allowed to enter the park until at least this Sunday. Fires in Lake and Mendocino Counties have prompted evacuations of residents there.

While such intense wildfires are obviously terrifiying for people living near them, they’re also worrisome for those living downwind hundreds of miles away. Exposure to wildfire smoke is a serious public health risk. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention warn that exposure to smoke “can hurt your eyes, irritate your respiratory system, and worsen chronic heart and lung diseases.” The CDC cautions that children, the elderly, and people with asthma and other respiratory conditions are especially at risk. The current fires have led to hazardous air warnings in parts of southern Oregon and northern California.

Wildfires are a natural part of ecosystems in much of western North America. But record-high temperatures and drier conditions fueled by climate change are lengthening the fire season in many regions while also increasing the frequency of intense fires. More than half of the western states have experienced their largest fires on record in the last 20 years (though this may, in part, be a function of decades of short-sighted fire prevention).

During the the Sonoma/Napa firestorm last fall, says Ronald Cohen, director of Berkeley’s BEACON air monitoring project, the air quality in the Bay Area was similar to an average day in Beijing, where PM 2.5 concentrations are regularly six times higher than World Health Organization recommendations.

A longer and more intense wildfire season means that wildfire smoke will become even more of a health risk. “We have to assume every summer is going to be the worst summer we have ever had,” says Sarah Henderson, senior environmental scientist for the British Columbia Center for Disease Control. In British Columbia, the fire season is also getting longer, Henderson says. Normally fires burn about 980 km (600 miles) a year; last summer, more than 1.2 million hectares (nearly 3 million acres) burned. British Columbia was in a state of emergency for 70 days due to wildfire, the longest provincial state of emergency in BC’s history. More than 60,000 BC residents had to evacuate their homes.

In a longitudinal study of various cities in British Columbia, Henderson found that distributions of asthma medications increased considerably on high smoke days, by up to 7 percent. In general, people with respiratory or cardiac problems are more at risk during days with poor air quality, but even healthy people are vulnerable to headaches and respiratory problems.

Government health agencies are already preparing for a future with more wildfires. The British Columbia Lung Association public health department released a series of recommendations for residents on how to prepare for wildfire season, including making sure that buildings have up-to-date air filters, and encouraging them to purchase portable air purifiers. In Los Angeles—where officials have worked hard to regulate pollution from sources like ports, highways, and oil and gas operations—wildfires have significant impact on air quality. The California Department of Public Health website directs residents to follow CDC guidelines and utilize face masks with an N95 or higher rating if they need to go outside; they are available at many hardware stores. Officials recommend people check the fit, because a mask that doesn’t fit well can actually worsen the problem by making it hard for the people who wear them to breathe comfortably. Dr. Henderson suggests getting a N95 respirator face mask professionally fitted, if possible. Staying indoors on smoky days is also recommended.

During a smoke advisory last December, the Los Angeles Department of Public Health advised schools to suspend physical activities like gym, cancel after-school sports, and keep windows and doors closed. The department also warned residents to close windows, throw away any food that might have come into contact with the ash floating through the air, and check if their air conditioning units drew in air from the outside.

If the answer to the last one was “yes,” residents were told to turn off the air conditioning and and go to a library or shopping center to stay cool and safe. Places where large numbers of people congregate, like community centers, malls, and libraries, often have better-than-average air filtration systems. Designated clean air shelters have been put in place in parts of British Columbia, Oregon, and California. During last October’s Sonoma/Napa fires, a community center in Bodega Bay was used as a clean air shelter because of its proximity to the coast.

Chris Albinson, a resident of Sonoma, was so concerned about the impact of last year’s wildfires on people’s health that he purchased N95 masks for all of his neighbors. The Sonoma hardware stores were out of masks, so he headed south and bought masks at a hardware store off Highway 101—and then immediately turned around and headed back to his neighborhoood.

“I basically drove them to each of my neighbors, because I knew they didn’t have them, and they were sheltering in place and couldn’t leave their homes,” Albinson said. “Some of them had little kids. So I just tried to resupply them with some food, water, masks—all my neighbors that I knew needed them.”

During the October 2017 fires, the city of Sonoma tried to respond as quickly as possible to the fire, but the early days were difficult. “Those first 48 hours were so horrible,” Albinson said, “Probably the most toxic.”

Albinson’s experience is a warning, and a reminder, that one doesn’t have to be directly in a fire’s path to suddenly be in harm’s way.

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club