Today, the Sierra Club published a report on emerging financial tools that could allow utilities to exit non-economic coal while protecting both utility customers and investor interests. The report details the financial barrier to retirement and a slate of potential solutions.

Getting out of non-economic coal

Forty years ago, your business selling vinyl records was thriving. You bought an enormous house with a pool and a thick shag carpets -- and to buy it, you took out a jumbo mortgage with a whopping 10 percent interest rate. Every year you made some changes -- added a gazebo, wood floors, a carport, a new roof. And each time you took out another loan.

Today, your vintage records are still great, but business isn’t what it was, and you could use a more sensible house with just a little less upkeep. But when you go to market, you realize that the house is underwater. It’s just not going to sell at anywhere close to what you owe. The bank doesn’t want you to just walk away, so instead they offer a deal. Sell the house for what you can, and pay off the remainder on the loan. The bank offers that you can pay off the debt at a 4 percent interest rate over the next two decades, and you’ll keep your good credit -- and vinyl records. You sell the house, refinance with the bank, and are now ready to buy the home that you can more readily afford.

This refinancing scenario is not new for homeowners, but it is a concept that’s attracting attention in the electricity sector with coal plants that are non-economic to own and operate. Right now, utilities and their regulators are trying to figure out how to offload costly coal plants that carry massive debts. Like the business of selling records, the market has moved on and utilities with large coal plants have to figure out what to do.

One of the tools gaining traction is a process known as ratepayer-backed bond securitization, or just “securitization.” When done correctly, it can help utilities pay off the remaining debt of expensive coal plants, protect ratepayers from excessive costs, and provide a pool of transition funds for affected communities -- like the workers at the retiring coal plant.

Securitization is just one emerging method in a new box of financial tools meant to help utilities and customers transition to clean, cheaper technology -- like wind, solar, and batteries. To help explain these tools, the Sierra Club released a white paper that outlines the history of how utilities found themselves with coal plant debt and the solutions on the table to fix it.

Hold on, why do we need financial tools?

Just in case you missed the memo, existing coal plants in the United States are not economically competitive. These plants aren’t competitive today, and we shouldn't expect these plants to turn a profit in the future, either. Earlier this year, Bloomberg reported that about half of the U.S. coal fleet would fail were it not for ratepayers keeping them afloat. It’s like paying above-market rent because you’re not allowed to move.

And why are ratepayers keeping those plants alive? Because as a captive ratepayer, it turns out it's really hard to comparison shop, and the coal plant owners haven’t gotten around to telling their customers that the plants just don’t make sense anymore. In fact, the coal plant owners have a distinct incentive not to say anything at all. Under traditional rate regulation, utilities get reimbursed for all the fuel and maintenance -- what we call “pass through costs” -- and make a profit on any capital they invest in on behalf of their customers, such as new transmission lines or new boilers at a coal plant. In fact, that’s the primary way a utility makes money -- charging a “rate of return” on every investment. What it amounts to is that many coal plants have racked up a huge amount of debt -- not only the first investment in the plant itself 40 years ago but also hundreds of millions of dollars of upgrades, retrofits, and replacement parts. So we’re left with a problem when we want to retire this plant. Like our big, but slightly dated house, we have a lot of debt and not a lot of value. But like our housing choice, we know that we’ll be better off moving… if we can figure out how to pay off our debt.

This is the very real, but unspoken, barrier to an electric system transformation in the U.S. coal fleet. Investor-owned utilities -- which amount to about three-fifths of the U.S. coal fleet -- are just straight up afraid of losing investments. By not saying anything, a lot of utilities are quietly hoping the problem will just go away, or that regulators won’t notice. But every year the economics just get harder to justify.

But haven’t a whole bunch of coal plants already retired?

Yes. About a third of the U.S. coal fleet has retired already, and more have made commitments to come offline in the next five years. In fact, 2018 is set to become the second largest year of retirements yet. But the calculus is getting a lot trickier. Before 2012, the median retiring coal plant was just 70 MW -- old, inefficient boilers. Those plants were hard to justify even before gas prices crashed and renewable energy was at market parity. Between 2013-2016, we started seeing a whole host of retirements to avoid environmental regulations. The median coal plant being retired was 113 MW. But from 2017 and projected to 2019, coal plants that have committed to retire have a median size of 200 MW, and recently we’ve seen enormous plants slated for retirement, like Luminant’s Big Brown and Sandow plants (590 MW+ each).

Generally bigger plants hold more debt. For any given utility, taking the most marginal plants offline is an adjustment. Taking the bulk of your non-economic steam generators offline is a new financial challenge.

But today we’re seeing a world that many coal operators hoped wouldn’t transpire. Low market prices, abundant and cheap renewable energy, and the rapidly falling cost of storage have left even those larger, more-efficient coal units high and dry. Or underwater, depending on your preferred metaphor.

A sticky calculus for investor-owned utilities

There’s a common myth that coal plants built 40 or 50 years ago should have been paid off by now. After all, when we first built them, we set a 40-year payment, or depreciation, schedule and started making annual payments. But coal plants are not static investments. Generation owners pump hundreds of millions of dollars into the maintenance and continued upgrade of the coal plants. Between new turbines, boilers, superheaters, economizers, and every other piece of hardware that can be replaced, many existing coal units have almost as much outstanding capital as they did when they were new. A recent paper from Carbon Tracker estimated there was approximately $249 billion in outstanding “book value” for the existing coal fleet of 277 GW, or almost $900/kW -- almost the cost of a new generator.

When a regulated investor-owned utility takes a coal plant offline, it faces the risk that regulators -- either today or in the future -- will chose to disallow the remaining costs of the coal plant. Under traditional rate regulation, ratepayers only pay for the costs of assets that are “used and useful.” Arguably, a retired coal plant is not useful to ratepayers.

Investor-owned utilities are loath to accept the risk that substantial costs could be disallowed, but without a clear path to recovery, are left facing that risk, or fighting retirement (or even the narrative that coal might be non-economic). Utilities with substantial exposure today may be more inclined to just sit tight and hope that their non-economic coal units effectively go unnoticed or even misuse planning tools to give a false impression of their fleet’s value.

So how do we help investor-owned utilities find comfort in retirement? The blunt instrument of “accelerated depreciation” simply jams all of the remaining costs into the years before retirement, but this can impart rate shock. Hypothetically, a utility could ask a regulator to provide for recovery over an extended period post-retirement, but every year risks the ire of regulators and disallowance of remaining “non-useful” costs.

The proverbial win-win for non-economic coal

There is an alternative to paying of debt faster, and that is securitization, or more simply put, refinancing. Securitization, as described above, is essentially a new loan for the coal plant. But the loan isn’t to maintain the coal plant -- the loan is to allow the utility to walk away from the plant without slashing its investors. Going back to our home example, securitization is a new, long-term, low-cost loan that allows us to pay off our underwater mortgage when we move to a new home. This mechanism has attracted recent attention in a number of states, including Colorado, New Mexico, and Missouri.

So what actually is securitization? Ratepayer-backed bond securitization is a financial model where the utility swaps its remaining debt in a plant for a ratepayer-backed bond. Unlike a corporate bond, which is paid for by the utility and the ratings for which depend on the solvency of the utility, a ratepayer-backed bond is guaranteed by the ratepayers -- not the utility.

Rate-regulated utilities serve customers by maintaining and operating generation, transmission, and distribution infrastructure. But rate-regulated utilities make a profit primarily by acting as financial institutions. Utilities raise capital to acquire infrastructure to serve ratepayer needs, and make a margin on the capital outlay. The rate of return, or the interest paid by customers, ranges between about 7-9%. Typically about half of that interest is a payment on relatively low-cost corporate bonds (3-6%), and the other half is a very high-cost return on equity (9-11%). That return on equity forms the profit margin for the utility.

We call the securitization a “ratepayer-backed” bond because the payments on the bond are literally guaranteed by the ratepayers. By building the payments into rates directly, banks can offer a much lower rate for the bond, around 4%, then is otherwise demanded by the utility (7-9%).

This model works by paying back the utility (in whole or in part), providing a lower cost of debt to the ratepayers, and opening up new streams of revenue that can be used to help impacted communities transition -- all at a lower annual (and absolute) cost to ratepayers.

So why isn’t everyone doing this? Well these bonds are ratepayer-backed. And to make sure that they get a high credit rating (and thus are cheap), we have to guarantee that the bonds get paid -- that they’re non-bypassable. And that type of irrevocable charge usually requires legislation. The non-bypassable nature of the bond can also be seen as impinging on the ability of the regulator to adjust rates -- and thus must be approached carefully.

Does it work?

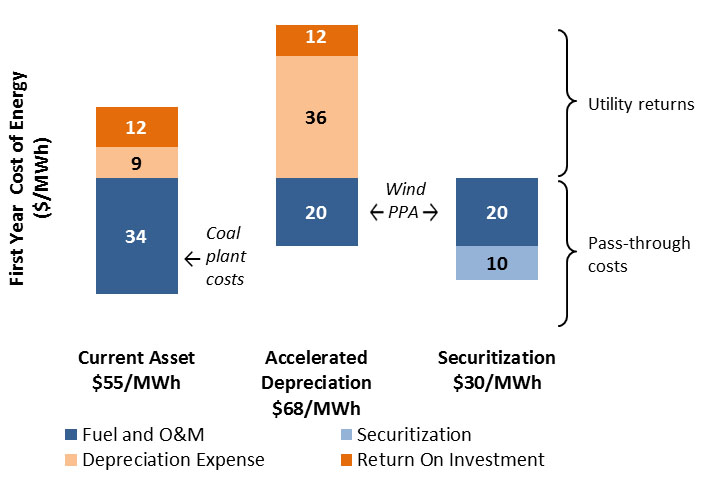

The schematic below illustrates the ratepayer impacts of securitization. Imagine a coal plant with $430 million dollars of remaining debt, and annual fuel and operating expense amounting to $34/MWh. In addition to those operating expenses, ratepayers are paying $9/MWh in depreciation expense (the payments on the capital) and $12/MWh on the rate of return (the interest on the capital), or a total of $55/MWh.

In our example world, the utility runs a request for proposals and finds inexpensive wind power purchase agreements (PPA) at $20/MWh – far cheaper than the $34/MWh coal plant. But to get the plant offline and take the wind PPA, the utility’s accelerated depreciation will crank up the annual depreciation expenses to $36/MWh. Overall, ratepayers would be paying $68/MWh just to take a non-economic coal plant offline.

In the securitization world, the utility swaps out its remaining asset $430 million asset base for a ratepayer-backed bond. The utility is paid back immediately and its risk goes to zero for the plant -- it can retire the plant and won’t face a disallowance or risk a regulator denying future debt payments. The utility still picks up the low-cost wind PPA, and ratepayers start paying off the bond. However, rather than paying an annual $21/MWh for the depreciation and rate of return, the ratepayers pay just $10/MWh to cover the costs of the bond. Ratepayers walk away having reduced their payments from $55/MWh for the coal plant to $30/MWh for wind power.

Does this solve the problem for the utility completely? No. The utility now has its cash back, but it lacks an investment for which its investors get a return. In some cases, utilities might want to try to couple securitization with capital recycling -- i.e. using some of the returned capital to acquire new clean energy resources.

And securitization is just one of a new slate of emerging tools. In future blogs we’ll try to explore other solutions and case examples, like Colorado’s use of cheap renewable energy to pay off coal plant debt, Florida’s use of a one-time securitization bill to retire an expensive nuclear plant, and the emerging world of green tariffs and green bonds.

What’s the role of stakeholders in these emerging financial tools?

We can’t lose sight of the fact that utilities maintain a charge to, first and foremost, serve ratepayers and act in the public interest. And while these tools are meant to help utilities act in the public interest, stakeholders, ratepayers, and advocates play a key role in ensuring that utilities act prudently, competitively, and using the best information available. Moving the electric sector toward its lower-cost and cleaner outcome requires that stakeholders both work with utilities to find equitable solution and ensure that these new solutions don’t simply serve corporate interests at the expense of customers or the public interest. This is a call to utilities, regulators, and stakeholders: We’re all going to have to step up our game.

Our paper on emerging financial tools can be found here.