In June 2018, the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) struck down the rules that govern PJM’s “capacity market.” Through this market, PJM pays generators for their promise to be online and available to meet future energy needs. About $10 billion worth of payments change hands every year, making PJM’s capacity market the largest single auction of electric power in the country. Capacity costs are ultimately paid by the 65 million electricity customers in PJM’s 13-state region from the Mid-Atlantic to Great Lakes, amounting to about a fifth of what residents pay for generation.

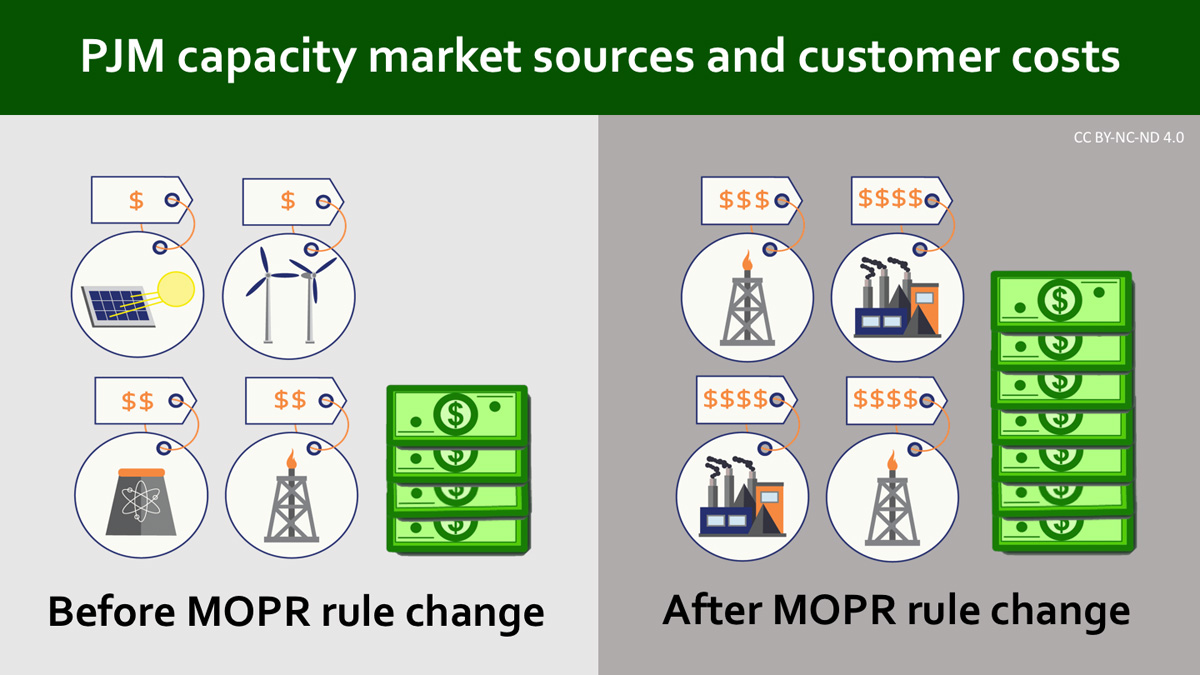

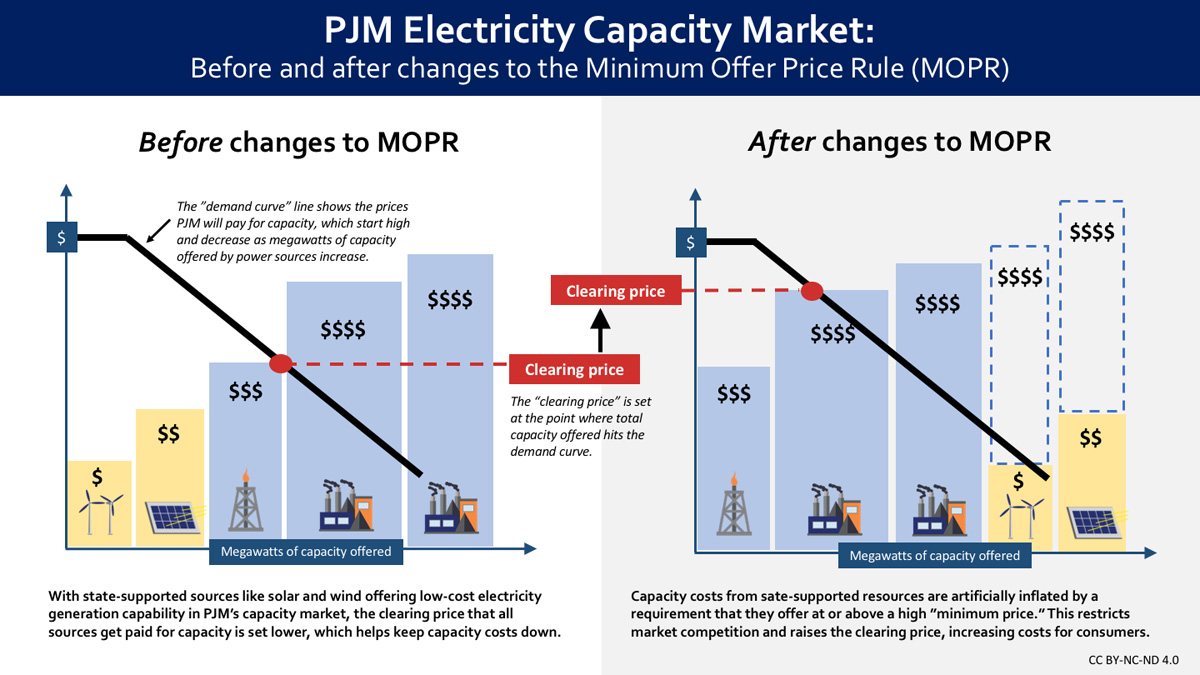

In the capacity market, generators “bid” their promise of power at the price it costs them to produce that power, with the lowest-cost bids chosen first. Clean energy sources are increasingly able to bid at a lower cost, as a result of both improving technologies and incentives from states that reflect the environmental and public health benefits of those sources. FERC issued its 2018 order on the grounds that PJM’s market rules did little to protect the revenues of some generators over others who receive such state incentives. Though FERC had initially committed to issuing replacement rules by January 2019, it has been largely silent this year.

All of that is expected to change with the departure of long-time Commissioner Cheryl LaFleur at the end of August. Close observers report that her absence will break a longstanding 2-2 deadlock at FERC and accelerate announcement of new market rules by October. Both generators and consumer advocates are on edge and rightly so: the new PJM market rules that FERC is poised to approve could spell bad news for both clean energy and consumers. A recent analysis by Grid Strategies shows that this new set of market rules could cost consumers in PJM’s region almost $6 billion a year, or about $50 to $90 per household annually, depending on location. This is on top of the billions consumers already shoulder for bloated capacity market costs. Overall, the largest states in PJM will pay an extra $1 billion, while seeing their incentivized new clean energy resources shut out of the capacity market altogether.

Image courtesy of Creative Commons

How did we get here?

In 2017, PJM engaged its stakeholders in a discussion of how capacity market rules might need to change to address state clean energy incentives that some believed were suppressing capacity market prices. In essence, PJM and many of its incumbent generators argued that because renewable energy and some nuclear generators receive revenues under state policies to compensate for emissions-free generation, those generators are: (1) able to offer into the PJM capacity market at a lower price than they otherwise would; (2) that these cheaper offers resulted in a less expensive clearing price paid to all resources that cleared the capacity market; and (3) that this lower price was not just and reasonable.

Despite the majority of its stakeholders voting in favor of keeping current market rules in place, PJM went ahead and asked FERC to impose a kind of price penalty--what’s called a minimum offer price rule (MOPR)--on the capacity market bid of any resource that receives a state incentive. When subject to the MOPR, a resource can no longer offer at its actual price, but is instead forced to offer at an artificially high price that PJM deems correct. A resource bidding at this price will almost always be too expensive to clear the market. In effect, the MOPR rule would allow more expensive fossil fuel bids to appear to be lowest cost--giving them an advantage in the market.

Image courtesy of Creative Commons

The MOPR carries two dire consequences: first, clean energy resources will miss out on an important source of revenue, which could make clean energy policies more expensive for states to pursue; second, consumers will be required to buy expensive capacity they don’t need.

In June 2018, FERC agreed with PJM that a MOPR was needed in the region’s capacity market, but tentatively proposed a workaround mechanism to prevent consumers for paying twice for capacity and avoid undermining state policy. PJM and other parties proposed various market designs in response, not all of which would achieve a fair balance between preserving a robust wholesale market and accommodating state policies.

Cost to Consumers

According to the recent Grid Strategies report, a FERC decision to implement the MOPR without an effective workaround for state-supported resources could cost consumers as much as an additional $5.7 billion each year 1 in the first few years, which is a 60% increase over the already staggering amount those consumers are paying for capacity. The costs vary across states based on their proportion of PJM’s overall load. For example, the sliver of Michigan that is part of PJM, and which represents less than 1% of PJM’s overall load, would bear $25 million in additional costs, whereas PJM’s biggest state, Ohio, would see a $1.1 billion jump in its capacity costs. Costs could be much higher in certain states depending on the actual geographic distribution of these MOPR’d clean energy resources across the PJM footprint, since transmission constraints can drive pockets of higher prices in certain areas, such as Illinois and New Jersey. Even states without ambitious clean energy goals will face an increase in prices. For example, West Virginia could face an additional $167 million in capacity costs, while Kentuckians would pay an extra $121 million.

It also bears noting that although the MOPR’s primary effect is to undermine state policies that seek to compensate resources for their emission-free generation, it will also likely apply to coal-burning units such as the Ohio Valley Electric Corporation’s Kyger and Clifty Creek plants, and the FirstEnergy Solutions Pleasants Power Station in West Virginia, all of which receive out-of-market revenues or tax benefits under legislation recently enacted in those states. 2

Ultimately, all of these additional costs brought by the MOPR will make it harder for states to set the ambitious clean energy goals that we need to avoid the worst of climate disruption. Given that the federal government is moving in the wrong direction on climate, state action is critical.

There is still time for FERC to avoid this disastrous outcome. First, it can reconsider its decision to impose the MOPR on state-supported clean energy resources, acknowledging that when those resources offer into the capacity market at lower prices, this is an accurate reflection of out-of-market revenues they earn as a result of state efforts to correct for environmental impacts. Second, FERC could steer PJM and its members towards a carve-out mechanism that would allow states to fulfill its capacity needs outside of PJM markets without penalty--one that would give states ample time to modify their laws and regulations as needed to use the new carve-out.

Whatever decision FERC makes must be supported by the record in the case, and consistent with the Federal Power Act’s requirement that FERC protect consumers from excessive rates. A decision to impose nearly $6 billion in extra costs on PJM consumers, and undermine the effectiveness of state energy laws, all to boost capacity prices in a region that is already bloated with excess capacity, would be a breach of public trust. It would also create an even greater rift between state and federal policymakers at a time when we need them to work together to transform our energy economy.

____________________

Endnotes:

-

This amount is based on analysis done by PJM’s Independent Market Monitor, Monitoring Analytics, and assumes that approximately 24 GW of resources in PJM are eligible for and utilize the resource carve-out. Grid Strategies then takes the market monitor’s figure down to the state level, showing each state’s approximate share of the overall $5.7 billion price tag. The costs vary across state based on their proportion of PJM’s overall load. For example, the sliver of Michigan that is part of PJM, and which represents less than 1% of PJM’s overall load, would bear $25 million in additional costs, whereas PJM’s biggest state, Ohio, would see a $1.1 billion jump in its capacity costs. Costs could be much higher in certain states depending on the actual geographic distribution of these MOPR’d resources across the PJM footprint, since transmission constraints can drive pockets of higher prices in certain areas, such as Illinois and New Jersey.

-

https://www.wvpublic.org/post/pleasants-power-station-slated-receive-12-million-tax-relief#stream/0. Under PJM’s proposal, tax incentives aimed at promoting general industrial development would not be deemed a “material subsidy” that could trigger the MOPR; however the West Virginia law exempts facilities engaged in electric generation from the state’s business and occupation’s tax, shifting it outside of the safe harbor in PJM’s definition of state policies that can trigger the MOPR. See Initial Submission of PJM Interconnection, Docket Nos. ER181314, EL18-178 (consolidated), at 20-21 (See pro forma Tariff, Article I, Definitions.).