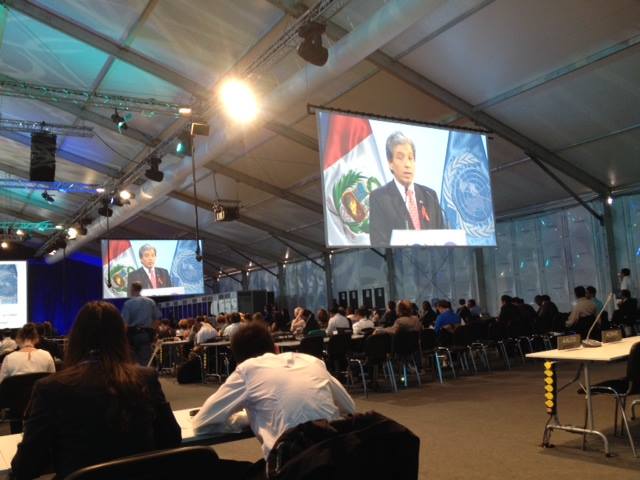

After once again going deep into overtime, the weary ministers at this year’s United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) international climate negotiations (COP) in Lima, Peru finally struck a deal.

Somewhat grandly styled the “Lima Call for Climate Action” by the Peruvian hosts, critics quickly derided the deal as more of a stage whisper, built as it was on non-binding provisions, vague guidance, and weak assessment mechanisms. Indeed, as a “call for climate action,” it was a far cry from the clarion call that rang out from New York in September, when the 400,000 participants in the People’s Climate March implored their leaders to take urgent action.

But while the outcome of the COP20 was not what many were hoping for, it did contain the basic building blocks for a more robust post-2020 agreement to be decided next year at COP21 in Paris. This year’s deal included a comprehensive draft of the negotiating text that will form the basis for next year’s agreement and could potentially resolve many of the key issues left unaddressed in Lima. And crucially, the deal makes clear that all countries are expected to present plans for their “fair and ambitious” contributions to the global effort to combat climate disruption in the first half of next year. No doubt, a lot of work remains to be done next year, but the Lima decision provides a solid stepping stone toward real climate action.

Still, there was reason to believe that the Lima negotiations could have achieved much more. Momentum coming into Lima positioned leaders well for a breakthrough. The climate marches in September put world leaders on notice that their citizens expect them to do something now to address the impending climate crisis -- and that the public would hold leaders accountable for how they responded.

Some leaders also began to make the same point to their peers. World leaders pressured Australian Prime Minister Tony Abbott for trying to keep climate disruption off the agenda of the G-20 summit in Brisbane and for stating that Australia would not contribute to the Green Climate Fund (GCF). President Obama offered a personal rebuke by announcing the U.S. contribution to the GCF in Brisbane.

As a result, Australia was forced to quickly retreat on both fronts, demonstrating that countries that seek to free ride on the global climate effort may pay a significant diplomatic cost. Of course, Australia’s pledge to the GCF turned out to be relabeled foreign aid from existing programs, but their grudging response to intense international pressure shows that even the most fossil-bound governments have to respond.

Perhaps most importantly, there were indications that the rigid political fault lines between the developed and developing world that had long bedeviled past negotiations were beginning to erode. The joint U.S.-China announcement on mitigation targets in November, pledges to the GCF from developing countries, and Brazil’s innovative proposal to reframe the problem of differentiated responsibility all signaled that countries were exploring new paths through the difficult morass of North-South politics.

Unfortunately, this momentum could not be converted into a game-changing outcome in Lima. This was mostly a result of the peculiar dynamics of the negotiations. While the issues on the table in Lima were certainly consequential, the negotiators all knew that the key issues will likely be resolved as a package next year in Paris, so there was little incentive to make a major move. Better to bet small until others show their cards than to go all in.

We’ve seen this pattern before -- the COP before a major meeting rarely produces significant progress. History shows that very little was decided at the COPs in the year before Kyoto (1997) and Copenhagen (2009).

So what was decided in Lima, and where does it leave us on the road to Paris?

First, as noted, the ministers agreed on a comprehensive text to use as the basis for negotiations next year. It runs to 37 pages because it includes all the variations submitted by Parties. Everything is now on the table to negotiate the compromises that will be essential to reach a final outcome next December.

Here, a critical option that has received significant support from Parties is a commitment to phase out most carbon emissions by 2050 and to achieve net zero carbon emissions by the end of the century. This would send a critical signal to investors that new investments in carbon intensive infrastructure are unlikely to pay off and that clean energy investment is a much better bet.

Nicholas Stern, the lead economist of the UK Stern Report, says the important thing is where the $4 trillion of new infrastructure investment – transportation, electric power sector, buildings, industry – will go in the next generation.

Will the world stay with fossil fuels or swing decisively to clean energy?

The battle is immense. The dirty fuels industries have enough coal, oil, and gas in the ground to continue claiming they can fill the need. But if they win, the planet will irrefutably cook by the end of this century.

Clean energy offers a much better deal – not only reducing greenhouse emissions but stabilizing energy prices and growing the global economy, dramatically reducing health and environmental impacts, and providing the potential for sustainable development in even the lowest-income countries.

In Lima, the requirements of a flexible and effective global deal focused on three big issues: information, pre-2020 finance, and “differentiation.”

Information: Last year in Warsaw, countries agreed to put their “intended nationally determined contributions” (INDCs) to the post-2020 global effort on the table well before negotiations commenced in Paris. This was designed to afford time for countries to evaluate, compare, and discuss each other’s proposals.

This year, they were expected to decide what information the INDCs would include to facilitate transparency and comparability. A key “scope” question involved whether INDCs would refer only to mitigation efforts, as developed countries wanted, or also include financial support for developing countries and recognition for adaptation efforts, as developing countries insisted. Finally, there was debate over whether and how countries would formally discuss each other’s proposals.

The Lima agreement would have included strong provisions on each of these elements, but various countries objected to key pieces, and the resulting takeaways reduced everything to the bare minimum. Developed countries did not want to specify how much money they would pony up after 2020, so finance was out. High-emitting developing countries did not want to be told what information to include in their INDCs or have a real discussion about them. So the guidance became vague and voluntary, and the review process was eliminated. Only adaptation reporting was sufficiently inoffensive to survive intact, but even that is basically voluntary.

Pre-2020 Finance: Much of the buzz regarding finance ahead of Lima concerned the initial pledges of about $10 billion over four years to the Green Climate Fund. While all Parties recognized this as welcome progress, it also amounted to just 2.5 percent of the $100 billion that developed countries promised in Copenhagen to mobilize each year by 2020. Even recognizing that this money could leverage much greater flows of additional capital, this still left huge amounts unaccounted for. Thus, developing countries understandably sought clarity on how developed countries would scale-up their contributions to meet their Copenhagen pledge. But language that would have directed developed countries to provide a roadmap on how they would scale-up finance was stricken from the final agreement.

Differentiation: Lurking behind the issues of finance, information -- and really, everything else -- was the potential show-stopper issue of “differentiation” from the core principle in the UN Framework Convention on climate action according to “common but differentiated responsibilities and respective capabilities.”

The Convention divided the world into two camps—developed countries which have obligations to take the lead on addressing climate disruption, and developing countries which must respond in a context of sustainable development. The Kyoto Protocol solidified this in binding emission reduction commitments for developed countries for an initial period from 2008-2012, creating the so-called “firewall.” Developed countries have long argued that this binary approach is no longer tenable and should not be carried forward into a new agreement.

Since Copenhagen, Parties have been groping their way toward a new regime that could define responsibility in a more nuanced manner while still recognizing the disproportionate responsibility and capabilities of more developed countries. Some are calling this “flexible” or “dynamic” differentiation. Towards this end, at COP17 in Durban, South Africa in 2011, they agreed that the Paris agreement would be “applicable to all” under the Convention principles of “common but differentiated responsibilities and respective capabilities.” And at COP19 in Warsaw, Poland last year, they agreed that “contributions” -- a less legally precise term than “commitments” would be nationally determined – that is, from the bottom up, and not based on a top-down fair-shares formula connected to a scientific view of required emission reductions. In Lima, this lack of clarity on the way forward impeded progress on a variety of issues, especially post-2020 finance and the reporting and review of contributions.

Differentiation – how climate response will be shared in a fair way -- is one of the more intractable issues in the negotiations and considerable work will be required next year to resolve it. The divide over the firewall and review issues was so deep that the Lima deal nearly collapsed on the final, extra day. In the end, language borrowed from the U.S.-China announcement in November papered over the gap. The INDCs will now be based on “common but differentiated responsibilities and respective capabilities, in light of different national circumstances.”

The inclusion of the term “national circumstances” gives developed countries comfort that they are moving beyond the binary firewall, while being sufficiently ambiguous to assure developing countries that they will not have new obligations thrust upon them. It remains to be seen whether this formulation has broad enough support to be incorporated into the Paris agreement.

At the end of the day, the “Lima Call for Climate Action” only moved us a small step toward a Paris agreement, let alone towards climate stability. But it did create enough space for all countries to come forward with “fair and ambitious” pledges next year without having to abandon cherished principles or untangle conflicting red lines. That may have been all that could have been achieved in an “off-year” COP, but it sets up quite a reckoning in Paris.

Now that the firewall has been lowered, the core question of differentiation will be front and center.