Athens County, Ohio, is the recipient of nearly 3 million barrels of toxic, radioactive fracking waste every year, almost 80 percent of which is from out-of-state. With the addition of an eighth injection well permitted in March, that amount is expected to rise to 4.4 million barrels per year, making it the number one acceptor of fracking waste in the state of Ohio. Many Ohioans may be unaware of the health risks waiting outside their homes from an industry known for its lack of transparency.

To combat this issue, the Athens County Fracking Action Network (ACFAN) met with the Athens County Commissioners in late June to draft a resolution declaring a moratorium on injection wells in Ohio. It is ACFAN’s hope that the measure will inspire other Ohio communities to pass similar resolutions, triggering Ohio legislators to push the moratorium at the state level.

“We can’t just send paperwork to the governor, we have to have some real action plans - the legislature has to see that this just isn’t something that can be ignored,” said Roxanne Groff, Bern Township Trustee and ACFAN member. “The voices of our communities are getting louder and stronger.”

The resolution communicates the commissioners’ frustration that with each new injection well permitted in the county, a public comment period is requested by citizens but repeatedly denied by the Ohio Department of Natural Resources.

The resolution also speaks strongly to the environmental degradation caused by injection wells in the already poverty-stricken Appalachian valley.

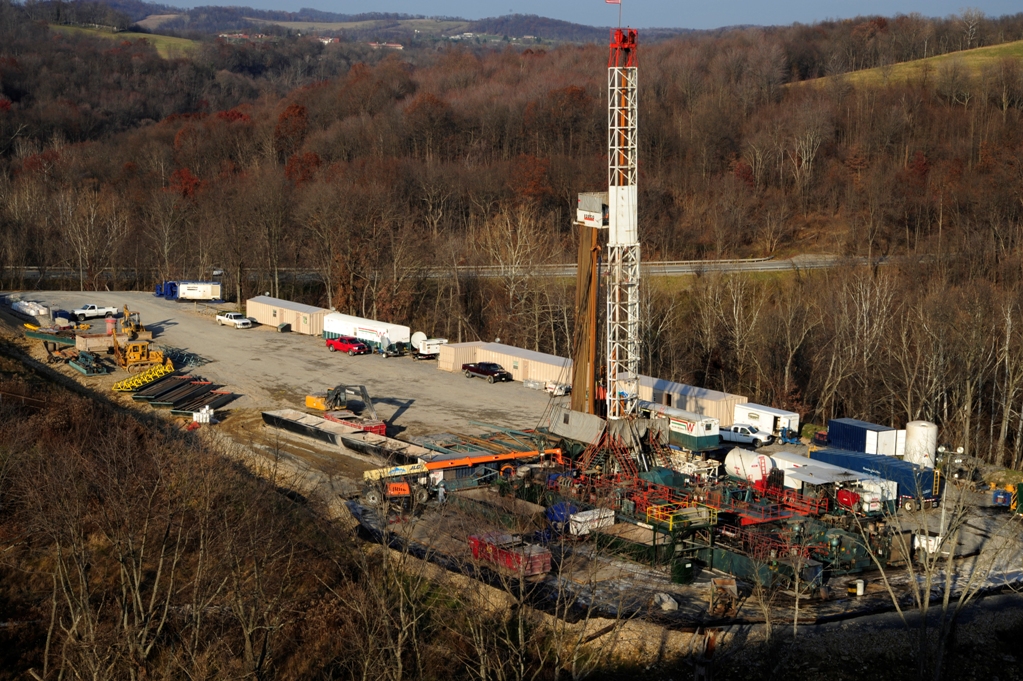

“The County Commissioners... have found that hosting Class Il injection wells provide no known benefit to the community, no guarantees of compensation, and no sustainable financial, business, or community betterment opportunities for the County,” the resolution reads. “These injection wells are threatening human health and the environment, threatening the health of streams and lakes, and increasing heavy tanker traffic on roadways, and threatening toxic spills and infrastructure damage for which the state does not hold industrial operators accountable.”

Twenty-one of 32 Appalachian counties are receiving all frackwaste that enters Ohio. Groff said it’s because Pennsylvania and West Virginia have stricter injection laws than Ohio, and it’s an easy way to bring money into the state.

However, Groff said Ohio has preempted significant community efforts by passing statutes and rules prohibiting local control.

“We’re sick of it - our citizens call on us as local elected officials to help, and we can’t help them,” Groff said. “It’s not fair, and it’s not right.”

Oil and gas industry waste is legally exempt from federal hazardous waste regulations and from parts of the Safe Drinking Water Act and Clean Water Act, and Class Il injection wells are notably under-regulated in Ohio. Additionally, aquifers in Athens County and the southeast Ohio region are not mapped, so the Ohio Department of Natural Resources cannot consider the impact on aquifers when permitting Class Il injection wells in the region.

But according to Ted Auch of fractracker.org, Ohio’s 1,530 drilled wells and 918 producing wells will waste 10-15 billion gallons of fresh water and produce 317-500 million gallons of fracking waste in the next five years if the trend continues.

Though successfully passing a statewide moratorium could be a stretch, ACFAN is hopeful given the power of community action. Groff pointed out that while moratoriums have passed in New York and Maryland, the fracking industry was not deeply ingrained in those states’ economies yet.

Even so, Groff believes in the power of county-passed moratorium resolutions.

“This is not the way citizens of the United States should live, across from a dangerous and potentially explosive situation without any sort of transparency to know what’s there,” Groff said. “That’s why we have to rely on the energy of community activist groups, like ACFAN, to support and create solutions wherever they can.”