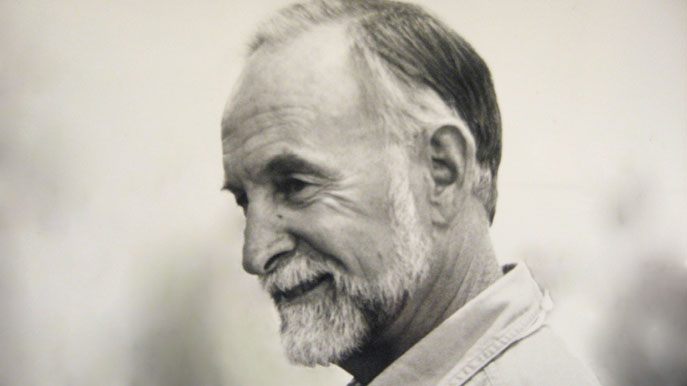

Royal Robbins in the 1990s (photo by Pat Ament, courtesy of Royal Robbins)

Legendary rock climber and outdoor-apparel entrepreneur Royal Robbins died on Tuesday, March 14, at his home in Modesto, California. He was 82.

Born in West Virginia in 1935, Robbins grew up there and in neighboring Ohio before moving to Southern California as a teenager with his mother. It was through the Sierra Club’s Angeles Chapter that the young Robbins was able to pursue rock climbing—a field that he would go on to transform.

Robbins’s climbing exploits were regularly featured over the years in the Sierra Club Bulletin, which would later become Sierra magazine. In 2011, he won the Club’s Francis P. Farquhar Mountaineering Award, honoring “an individual’s contribution to mountaineering and enhancement of the Sierra Club’s prestige in this field.” In accepting the award, Robbins reminisced about how he joined the Sierra Club in 1950 so he could be a member of the Angeles Chapter’s Rock Climbing Section, which was phased out in 1985 when insurance difficulties compelled the Club to suspend its technical climbing outings.

It was in Los Angeles at age 14 that Robbins was chosen as his Boy Scout troop’s “Outstanding Outdoor Scout," qualifying him to join other L.A.-area scouts for a two-week backpacking trip to the Sierra Nevada. The trip marked the start of a lifelong love affair with the out-of-doors.

Robbins dropped out of high school at age 16, but earned his diploma by attending night school at Hollywood High. He continued to refine his climbing skills over the course of a half-dozen years working as a bank teller in downtown Los Angeles and a two-year stint in the army. His reputation as an elite climber was cemented on Tahquitz Rock in the San Jacinto Mountains, where he made numerous “free ascents”—highly unusual at the time—in which the climber uses ropes and other climbing equipment only for safety and support, not to assist progress.

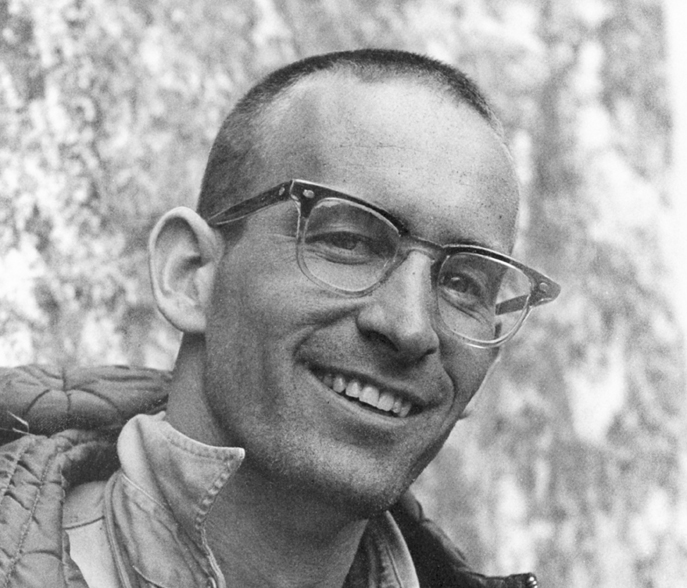

Robbins' spot in the rock-climbing pantheon was secured by his many first ascents and free climbs at Tahquitz, but like most elite climbers, he was inevitably drawn to the big walls of Yosemite, where in 1957 he and two companions became the first to climb the northwest face of Half Dome. Two years later, he was part of the second-ever ascent of The Nose of El Capitan, and the first to accomplish the feat in one continuous climb.

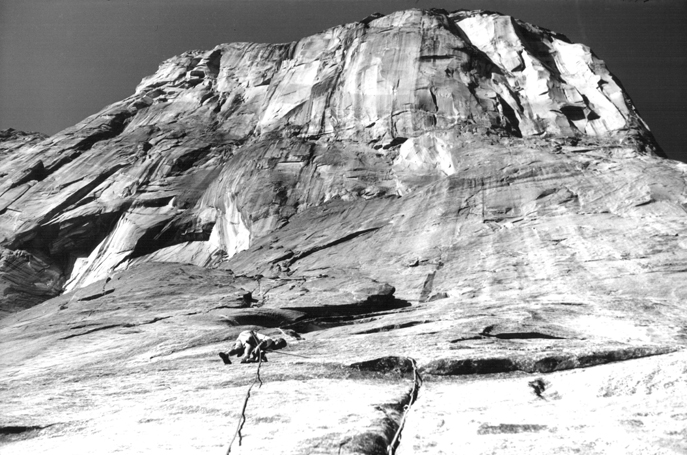

Below, Robbins makes his way up the face of El Capitan, one of the most challenging and renowned climbs in the world.

Royal Robbins climbing El Capitan (photo by Tom Frost, courtesy of Royal Robbins)

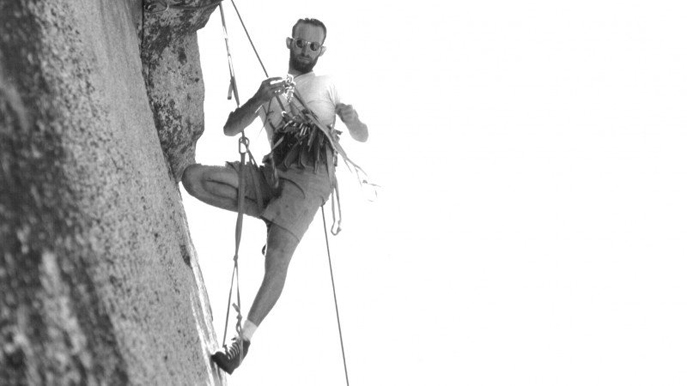

Robbins's inclination toward “clean climbing” evolved into a “leave no trace” philosophy that would come to distinguish his climbing career and legacy. He was among the first to advocate for the use of removable nuts for protection instead of driving bolts and pitons into the rock. As reported by the New York Times, “[a]s the popularity of rock climbing grew, Robbins became part of the sport’s consciousness, a powerful advocate for clean climbing, urging those who followed him up the rocks to leave few traces of their path.”

Robbins signaled his commitment to clean climbing by removing all the pitons he used on the ascent of The Nose. As Daniel Duane, author of several books on climbing, told the Associated Press, "If it hadn't been for Royal, all those cliffs would be a total mess."

Royal Robbins on the third pitch of the Salathé Wall, El Capitan (photo by Tom Frost, courtesy of Wikimedia Commons)

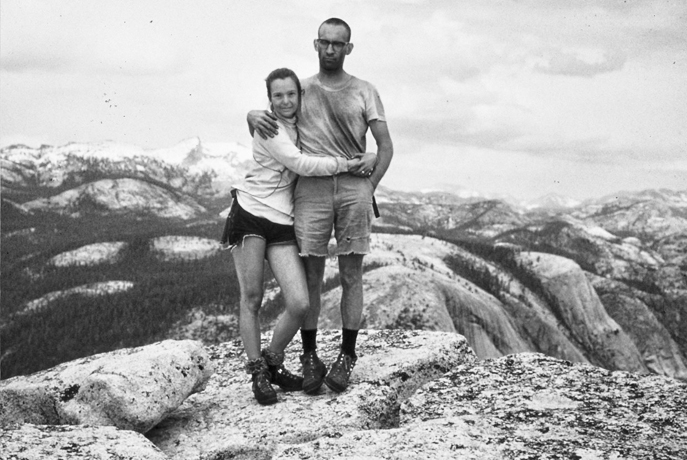

In 1961 at Camp 4, the notorious and ramshackle campground and climbers’ hangout near the base of Yosemite Falls in Yosemite Valley, Robbins met Liz Burkner, then working as a hostess at the toney Ahwahnee Hotel, scarcely a mile away. They married in 1963, and four years later—a decade after Robbins’ first ascent of Half Dome—the couple climbed it together, making Burkner the first woman to accomplish the feat.

Liz and Royal Robbins atop Half Dome in 1967 (photo courtesy of Royal Robbins)

Following a two-year stint in Leysin, Switzerland, and climbing and river-running sojourns in the Alps and the Andes, the couple returned to the U.S. and settled in Burkner’s hometown of Modesto, California, a two-hour drive from Yosemite. In 1969 they started Rockcraft, a climbing school, and Mountain Paraphernalia, a climbing-gear business. The latter endeavor gradually morphed into an “active lifestyle apparel” company, eponymously named Royal Robbins after its cofounder. The company, which emphasizes environmental and social responsibility, remains extant, hugely successful, and headquartered in Modesto.

(Read An Open Letter: Together We Can Defend Our Public Lands, signed by Royal Robbins and more than 100 other companies in the outdoor industry.)

Robbins took up kayaking in middle age in the mid-1970s, and made several first descents of wild rivers in the Sierra Nevada. In the early 1980s, he and his whitewater companions made the first descents of the San Joaquin, Kern, and Kings Rivers, and the Tuolumne River between Tuolumne Meadows and Hetch Hetchy Reservoir. Over the course of his kayaking career, Robbins made more than a dozen first descents in California and over a dozen more in Chile. He also ran rivers in Norway and Russia, and was among the first Westerners to run the Bashkaus River in Siberia.

Royal Robbins kayaking in the Sierra Nevada (photo courtesy of Royal Robbins)

Robbins was featured in the 2014 documentary film, Valley Uprising. Greater detail on Robbins’ climbing career can be found here, here, and here, and on this timeline.

The Planet will give the last word to Royal himself:

“We need adventure. It’s in our blood. It will not go away. The mountains will continue to call because they uniquely fulfill our need for communion with nature, as well as our hunger for adventure."