By Bekah Hinojosa

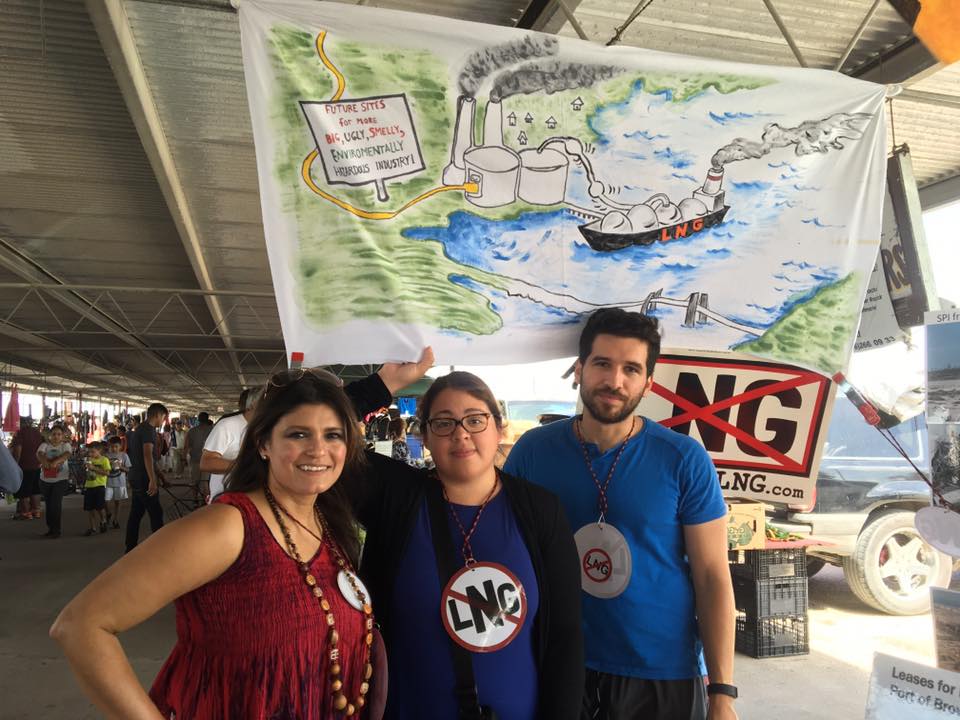

I can trace back my mother’s Tejano and indigenous family more than six generations to a tiny cemetery in the Rio Grande Valley community called Encantada-Ranchito-El Calaboz. On my father’s side in another Valley town, I can trace back four generations. The Valley is my place of origin and where my ancestral heritage and legacy is located. Because of that, and for many other reasons, I became a community organizer. Now, I am fighting to protect my native lands from the construction of three giant, polluting liquefied natural gas (LNG) export terminals. These terminals have been proposed for the Port of Brownsville and the companies behind them have plans to build massive natural gas industrial complexes and bulldoze pristine lands filled with the remains of my ancestors.

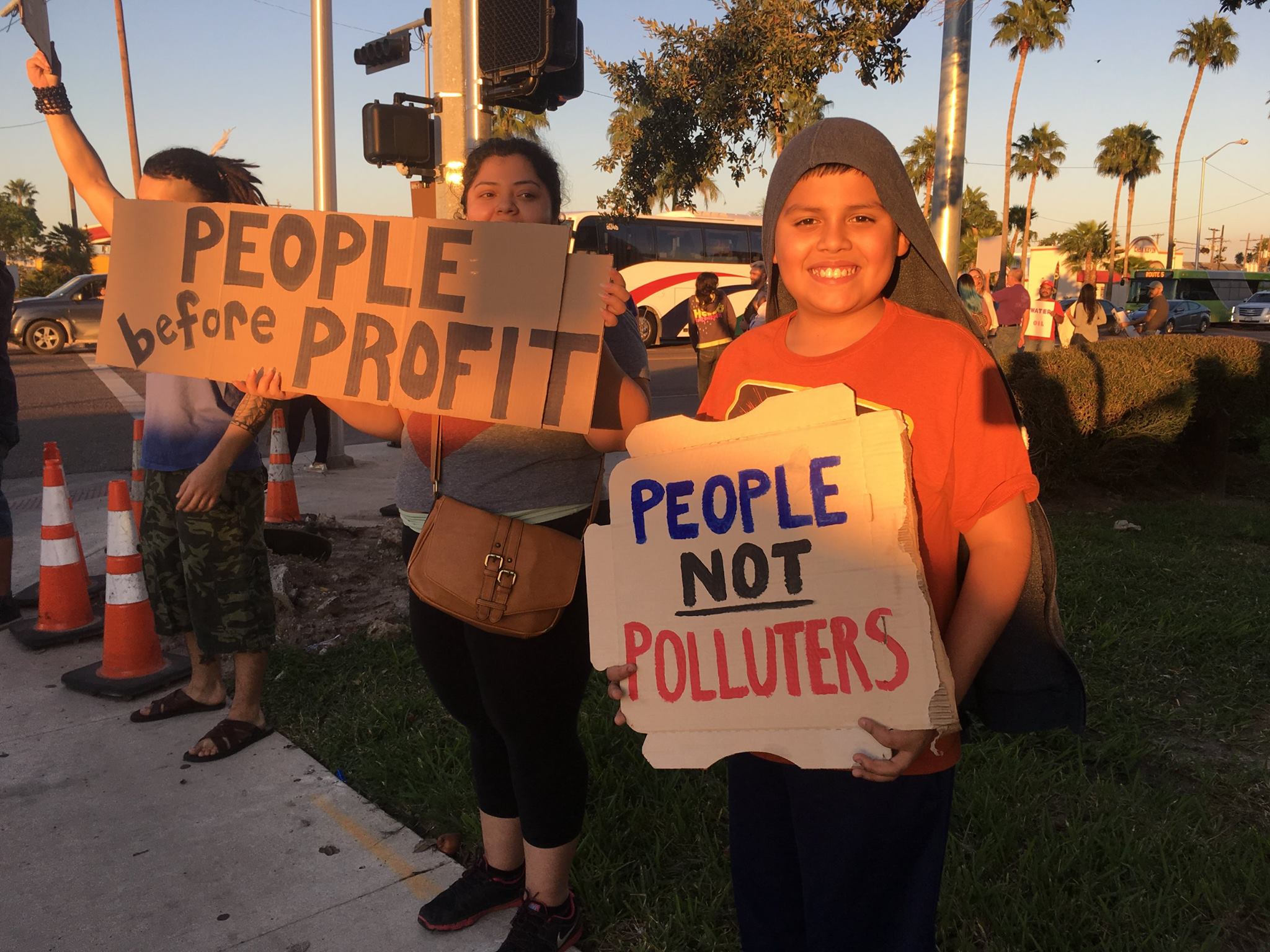

The Rio Grande Valley is a largely Latino region that has many impoverished communities. More than 1.3 million people live on the double frontlines of Texas: the U.S./ Mexico border, where families are forcibly separated, and the Gulf of Mexico, waters which are also exploited by oil and gas drilling for overseas exporting.

Growing up here, our public schools did not offer much knowledge about local Tejano history and even less about the indigenous culture of my mother’s family. As any follower of Texas’ Board of Education can attest, racism also manifests in our public education system. More than a hundred Texas historical markers can be found across the Valley, yet not a single marker is dedicated to the struggles or accomplishments of Tejanos and our Indigenous peoples. Instead, all the markers are dedicated to the wealthy white landowners that colonized the region.

If these LNG terminals are approved by the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC), it would be an act of environmental racism. The facilities will span more than 3,000 acres near low-income Latino neighborhoods. These neighborhoods will have to deal with the towering storage tanks filled with flammable gas, tall polluting flare stacks, new natural gas pipelines, and massive tanker ships that could clog up the ship channel (potentially destroying the livelihood of local shrimpers).

A History of Cultural Disrespect

Eduardo Martinez, a Barrio Historian and writer at Pharr from Heaven, interviews older Tejanos to collect local stories and feels that knowledge of indigenous roots is lacking.

Eduardo Martinez, Barrio Historian. photo credit: Raul Robert Perez

“This situation with the LNG company wanting to build on a burial ground reminds me of a story back in 2013 that happened in my hometown of Pharr. There were some bones of indigenous people found at a construction site. The company moved the bones and they were eventually reburied nearby. I really hope that this LNG company has some dignity and respect and doesn’t build on this indigenous burial ground. We have had so much history erased here in the Valley, and to build on this specific spot would just be continuing that tragic practice,” remarked Eduardo. Moving remains is highly disrespectful to native burial traditions and is an act of desecration.

The lack of knowledge about the Tejano and indigenous peoples of the Valley is a big problem but an even bigger problem would be erasing the opportunities and the sites critical to learning about and understanding these cultures. One site that could be potentially erased is what archeologists call the “Garcia Pasture.”

Intentional Bad Job?

Texas LNG, one of the companies proposing an LNG terminal, submitted a 92-page document located deep in the FERC website called “Resource Report 4: Cultural Resources.” The report outlines the company’s efforts to contact numerous Texas tribes to gather information about the Garcia Pasture site. Based on the report, however, Texas LNG failed to contact the Carrizo Comecrudo Tribe of Texas, the tribal group that originates from the South Texas Rio Grande Delta.

When asked about this oversight, Juan Mancias, Chairman of the Carrizo/Comecrudo Tribe of Texas, said that the tribe contacted FERC concerning other native sites in Texas. “The Carrizo/Comecrudo Tribe of Texas is concerned about the preservation and maintenance of the oldest language and its cultural lifeways. Ignoring the presence of the original people is to promote the ongoing Genocide. We will stand against the genocide that continues to plague the Esto'k Gna (Carrizo/Comecrudo Tribe of Texas). We ask that they stop ignoring the Native Original People of Texas pleas and to protect our sacred lifeways and sacred sites.”

The resource report also severely downplays the importance of the site and fails to include the fact that remains have already been excavated: an indigenous cemetery, remains of a pre-columbian village, and many artifacts from nomadic cultures. The National Park Service has come out to express their concerns that “[Texas LNG] did not do a thorough enough job in researching and understanding the Garcia Pasture site, nor the prehistoric archeology of the Rio Grande Delta and deep South Texas.”

Rolando Garza, a local Brownsville archeologist with the National Park Service, has said that, "The Garcia Pasture Site is one of the premier prehistoric archeological sites in Cameron County.” In his opinion, “this site warrants long-term preservation."

Annova LNG, another LNG company, has also submitted a “Cultural Resources Report,” and their site will desecrate another area where treasured pre-columbian artifacts have been found.

Conflict of Interest

Texas LNG’s Cultural Resource report has a “plan for the unanticipated discovery of cultural resources and human remains during construction.” This plan involves training one of their company staff members to identify “cultural resources and human remains,” halting construction should they encounter remains, and finally “notify[ing] relevant authorities -- the Texas Historical Commission.” Essentially, identifying the remains of Valley indigenous culture will be the sole responsibility of the company that is seeking billions in profit by building over and destroying these cultural resources.

The indigenous peoples of the Rio Grande Valley are still here and protecting our history means fighting for untouched lands and preserving the ties to our culture. The decision to push back against the destruction of our land and culture here in the Valley is ours. We are proud to join tribes across the country like the Standing Rock Sioux, who have been standing up and pushing back against the desecration and theft of their land and multi-billion dollar fossil fuel companies who are reenacting colonization by polluting land and water.