The Most Important Environmental Stories of 2020

It may have been an awful, no-good year—but there were some silver linings

Photo by Will Lester/The Orange County Register via AP

Can we flip the calendar already? We had barely made it past January when the memes about how the days felt like weeks and the weeks felt like months began ricocheting around the internet. It only got worse from there: a deadly pandemic and international lockdown, police killings of Black Americans, climate-change-fueled extreme weather events that hammered from all directions, and a nail-biting US election that revealed how entrenched the divisions in American society are.

Yet even in the midst of all the bad news, there were encouraging signs of progress, especially on the environmental front. The transition to clean energy showed signs of accelerating, environmental groups notched some major wins against fossil fuel projects, and the movement as a whole demonstrated a renewed commitment to forging alliances with social justice organizations.

Here are some of the happenings and trends of the past 12 months that are likely to have a ripple effect for (hopefully happier) years to come.

Photo by ekolara/iStock

COVID-19 Reveals That It’s All Connected

The COVID-19 pandemic is likely to be among the biggest stories of our entire lives, full stop. What started as a novel coronavirus outbreak in a midsize Chinese city eventually swept the globe, paralyzing life as we knew it, grinding economic activity to a halt, and, as of this writing, taking some 1.7 million lives around the world, including more than 300,000 in the United States alone.

The environmental dimensions of the pandemic haven’t received as much attention as they could’ve and should’ve, but the fact is that COVID-19 also illustrates the basic tenet of ecology about interconnectedness. “When we try to pick out anything by itself, we find it hitched to everything in the universe,” Sierra Club founder John Muir famously wrote, and the pandemic made that truth plain. It revealed the interconnectedness among nation-states in a globalized economy and the interdependence of people within countries—how one person’s seemingly innocent maskless hangout can become a deadly super-spreader event. The pandemic’s origins also show how human civilization remains hitched to wild nature.

As wildlife journalist Rachel Nuwer wrote in a recent Sierra cover story, “The virus that causes the disease … almost certainly sprang from the commercial wildlife trade.” SARS-CoV-2 is a zoonotic disease that jumped the species barrier, and that leap was facilitated by humans’ disruption of ecosystems. The wildlife trade is part of that—and so are deforestation, habitat fragmentation, and the conversion of wildlands to agricultural fields—all activities that can spark a “spillover event,” as author David Quammen has warned about for nearly a decade.

“We can exploit nature,” Nuwer wrote, “but at some point there will be serious repercussions for our species as well.” The pandemic has afforded humanity a historic opportunity to rethink our habits of exploitation and to reset our relationships to the rest of life on Earth. It remains uncertain, however, whether we’ll take advantage of this opportunity—or else continue on with the deadly business of business as usual.

Photo by Pavlo Gonchar / SOPA Images / Sipa USA via AP Photos

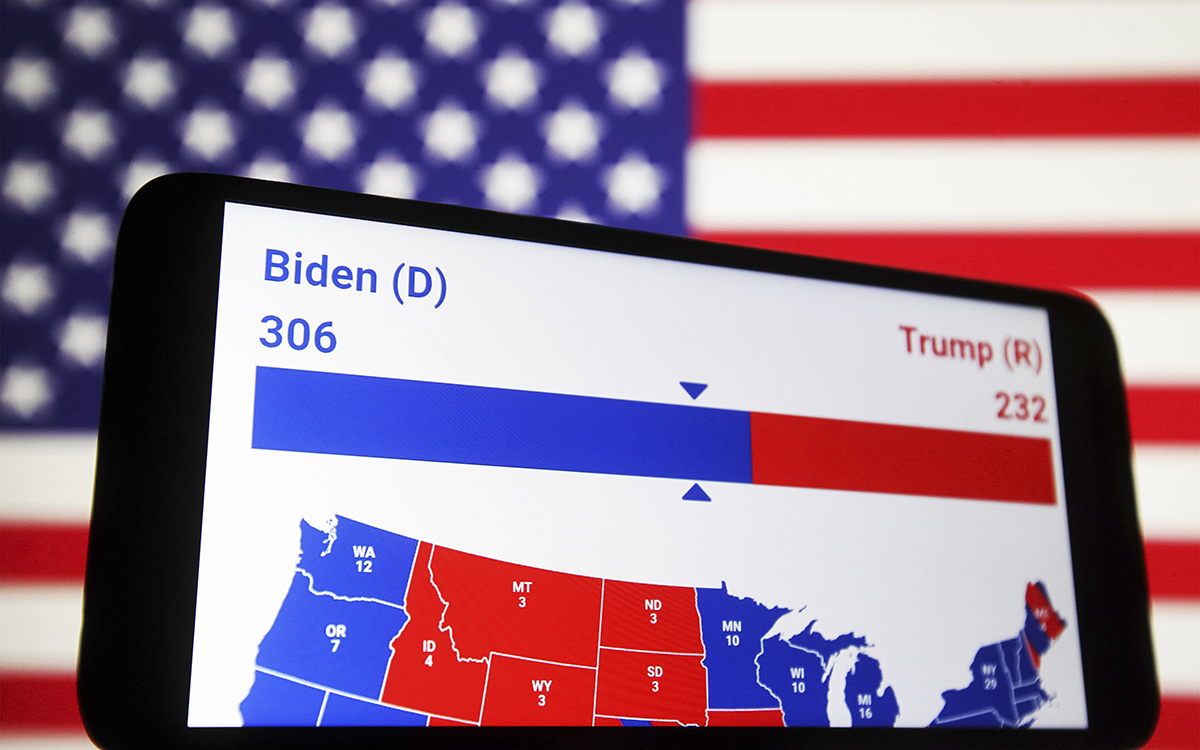

Trump Gets Dumped

Just as the pandemic is likely to be among the biggest stories of our lives, the 2020 US elections will be remembered as one of the most consequential political contests in modern US history. Despite the pandemic and Republicans’ coordinated efforts to suppress turnout, more than two-thirds of eligible voters cast a ballot, a record-shattering figure and the highest turnout in 120 years.

The election was, of course, primarily a referendum on Donald Trump—that sociopathic, racist, misogynistic, failed real estate developer who has been a kind of succubus on the dark underbelly of the American id. It was also a referendum on whether the US president would completely ignore the climate crisis or move boldly to address it.

For anyone who truly cares about the environment, Trump’s defeat is obviously good news. His one term has been marked by an all-out assault on environmental protections. His administration spurred an oil and gas rush on public lands, withdrew from the Paris Agreement, attacked fuel economy rules, stripped protections for wolves and grizzly bears, and sought to weaken bedrock laws like the Endangered Species Act and the National Environmental Protection Act. (Though it’s worth noting that the Trump administration has had a lousy record in court, losing some 80 percent of environment-related cases.)

Just as important: 2020 marked the first time that climate change was a central part of the presidential contest. Climate was a major topic at all of the vice presidential and presidential debates, the final of which even featured a question (the first ever!) on environmental justice specifically. Joe Biden unapologetically campaigned on a climate platform, and in his stump speeches repeatedly referred to the climate crisis as among the most pressing threats facing the United States. According to exit polling by Morning Consult, nearly three-quarters of Biden voters said that addressing climate change was “very important” to their vote. A fifth of Trump voters said the same.

It’s very likely that, in hindsight, 2020 will be viewed as the emergence of the long-awaited “climate voter”—someone whose vote is largely influenced by, maybe even determined by, whether a candidate is a climate action champion. As Sierra Club executive director Michael Brune said at a press briefing a few days after the election, “President Biden and Vice President Harris will have a decisive mandate to act with great strength and great clarity on climate change and protecting our air, and our water, and our communities.” Now, it’s up to the environmental voters who helped put the new administration in power to make sure that it makes good on that mandate.

Photo by Will Lester/The Orange County Register via AP

The World Is on Fire

Climate change became a central issue in the US elections, in part because its effects are now so front and center that they are impossible to ignore. Exhibit A: the fires that swept the globe once again this year.

The fires began in January, in the midst of austral summer, and never really let up from there. In the first month of the year, fires tore across the eucalyptus forests of Australia that had been left bone-dry by a scorching heat wave. Some 12 million acres were burned, at least 25 people lost their lives, and an estimated 1 billion animals perished in what Australian intellectual Clive Hamilton, writing for Sierra, called “a wildlife holocaust.”

Then, in June, fires swept through the Siberian tundra as parts of Russia’s far north experienced record-breaking temperatures above 100 degrees Fahrenheit.

The fire season in the American West was once again brutal. Fires slammed through Colorado, eastern Washington, and Oregon, where some conflagrations even reached into “asbestos forests”—so named because it was thought they were too wet to burn. California broke yet another record for acreage burned, as some 8,200 fires lit up more than 4 million acres. At one point, the smoke was so heavy over the San Francisco Bay Area that it felt like “darkness at noon.” And while many North Americans were transfixed by the dystopic images coming out of Oregon and California, Brazil once again had a nightmarish fire season as land grabbers pushed farther into the Amazon Rainforest.

At this point, record-breaking fire seasons are part of the new normal of climate change. And, in fact, some biologists say that the fires are ushering in a wholesale transformation of global ecosystems. In Colorado, for example, trees aren’t regenerating in some post-burn areas—and this may be just the first glimpse of forests turning to chaparral and chaparral transforming into grasslands or deserts. With our fossil-fuel-fueled fires, civilization is remaking the planet. Speaking in early December, UN Secretary-General Antonio Guterres summed up our current situation in the bluntest terms possible: “Humanity is waging a war on nature. This is suicidal.”

Photo by Eli Hartman / Odessa American via AP Photos

Big Oil Melts Down

It would be heartless to try to find any kind of silver lining in the COVID-19 pandemic. Yet the coronavirus has led to at least one clear environmental good: the diminishment of the global oil industry.

As energy journalist Antonia Juhasz wrote in Sierra’s September/October cover story, the pandemic-driven lockdowns of the spring and early summer incinerated global oil demand—and quickly led to a meltdown for the international oil markets, with petroleum at one point trading at negative values. While oil demand has partially rebounded, the industry’s future prospects look bleak. “The global oil industry is in a tailspin,” Juhasz wrote.” It is clear that the oil industry will not recover from COVID-19 and return to its former self. What form it ultimately takes, or whether it will even survive, is now very much an open question.”

The evolution is well underway. British oil giant BP has announced that it is reducing its investments in the oil and gas industry and prioritizing renewable energy projects—all part of the company’s efforts to reinvent itself as a 21st-century energy enterprise. And while ExxonMobil isn’t making any similar moves, even this dinosaur appears to be recognizing that the world is moving on from its products. The company recently wrote down the value of its oil and gas fields by $20 billion, and it is planning on cutting 15 percent of its workforce.

Financial markets are also coming to recognize the new reality. As recently as 2013, ExxonMobil was the biggest company in the world as measured by market value. Today, it’s not even among the 40 biggest most-valuable companies in America. Tesla, the electric vehicle manufacturer, has a market capitalization some three times bigger than the oil company's.

It’s very likely that a few years from now, we will look back on 2020 as the beginning of the end for Big Oil.

Photo by extreme-photographer/iStock

California Commits to Phasing Out Internal Combustion Vehicles

The fact that Tesla now has a greater market valuation than ExxonMobil isn’t just a sign of the oil industry’s weaknesses; it’s also an indication of the strength of the ascendant electric vehicle industry.

Tailpipe emissions from cars and trucks now constitute the largest slice of US greenhouse gas emissions—which means that there’s no way to address climate change without electrifying the transportation sector (and ensuring all that juice comes from carbon-free sources). According to a recent study by researchers at Princeton, some half of US auto sales will have to be EVs by 2030 for the US to meet the goal of being net-zero by midcentury. While EVs still constitute just a sliver of US auto sales today, there are encouraging signs that the transportation industry is moving in the right direction.

The biggest news on this front came in September, when Governor Gavin Newsom of California signed an executive order directing the California Air Resources Board to put together regulations for every new passenger car and truck sold in the state to be zero-emissions by 2035. In other words, in 15 years, you won’t be able to buy an internal-combustion-engine car in the Golden State, the very birthplace of American car culture.

Manufacturers are already working to meet such mandates. GM and Ford each have a raft of electric models already in production or on the drawing board—including an electric version of the hugely popular F-150 pickup truck that has so much muscle it will put gas and diesel versions to shame, and a super cool, Joe Biden–approved electric Corvette. Equally important, major manufacturers like Volvo, VW, Daimler, and Tesla are racing to bring to market all-electric heavy freight trucks. Given that freight accounts for one-third of US transportation emissions—and contributes to death and disease in port and shipping communities—the eventual electrification of the freight industry would be a major win for both the climate and public health.

All signs point to a transportation future that promises to be clean, green—and fast.

Photo by pixinoo/iStock

Banks and Investors Bail on Dirty Energy

If you’re searching for more evidence of the rise of the clean energy industry and the steady decline of fossil fuel corporations, look no further than Wall Street. Yes, you read that right. Some of the country’s biggest banks and lenders are starting to tiptoe away from continued funding of the death economy.

After years of grassroots pressure from the Sierra Club, other grassroots groups, and Indigenous nations, JPMorgan Chase announced in February that it would no longer finance oil and gas extraction in the Arctic and would also stop financing many coal-related enterprises. Then, just a week later, Wells Fargo unveiled a similar commitment. The twin announcements were an especially big deal given that JPMorgan Chase and Wells Fargo have in recent years been, respectively, the first- and second-largest US-based financiers of fossil fuel projects.

These commitments, among others, clearly rattled the oil industry and its bagmen in Washington. In November, the Trump administration moved to prohibit banks from excluding fossil fuels from their portfolios. But that scare tactic didn’t stop Bank of America from following other lenders’ leads. Every major US bank has now ruled out funding Arctic oil drilling. And just last week, the venerable insurance company Lloyd’s of London said it would stop underwriting new investments in thermal coal, tar sands, and Arctic oil drilling.

Meanwhile, the global fossil fuel divestment movement continues to rack up important wins. In early December, the New York State Pension Fund—one of the world’s largest investment pools, with some $226 billion in its portfolio—announced that it will sell many of its fossil fuel stocks within the next five years.

These developments and others signal a sea change among big investors. When it comes to financing extreme energy projects, the smart money is heading for the exits.

Photo by Maksim Safaniuk/iStock

Pipelines Get Plugged

Banks and other lenders may be more reluctant to finance controversial fossil fuel projects in part because environmental activists are making such projects increasingly risky and expensive. Through a combination of on-the-ground direct action, lawsuits, and citizen pressure via state and federal commissions, environmentalists are raising fossil fuel companies’ cost of doing business and making dirty energy projects less attractive.

Case in point: The proposed Atlantic Coast Pipeline. For years, environmental group fought the fracked gas conduit on the grounds that it would increase greenhouse gas emissions, threaten the Appalachian Trail, and exacerbate environmental injustices. In July, the two main backers of the pipeline—southern utilities Dominion and Duke Energy—said they were pulling the plug on the project, marking a major victory for greens.

Also in July, a federal court ordered a shutdown of the hotly contested Dakota Access Pipeline (though an appeals court later allowed for the line to continue operations), and the Supreme Court knocked back an effort by the Trump administration to allow construction on the zombie-like Keystone XL pipeline. As Kelly Martin, director of the Sierra Club’s Beyond Dirty Fuels campaign, told Inside Climate News at the time: “A new era [is] upon us—one for clean energy, and one where the risks of fossil fuel infrastructure are increasingly exposed.”

Indeed. In November, Governor Gretchen Whitmer of Michigan revoked a crucial permit for the existing Line 5 pipeline and ordered it to be shut down by this coming May. Environmental groups and local residents continue to battle construction of the Mountain Valley Pipeline, which is just barely limping along as costs rise, and opposition has also stalled a proposed gas export facility in Oregon. And while Minnesota officials did greenlight Enbridge’s Line 3 oil pipeline, Indigenous water defenders have staged a series of blockades and protests to slow down construction.

You can expect these contests over fossil fuel infrastructure to intensify and expand in the coming year, especially as environmental groups set their sights on preventing increased oil and gas exports out of North America.

Photo by AP Photos

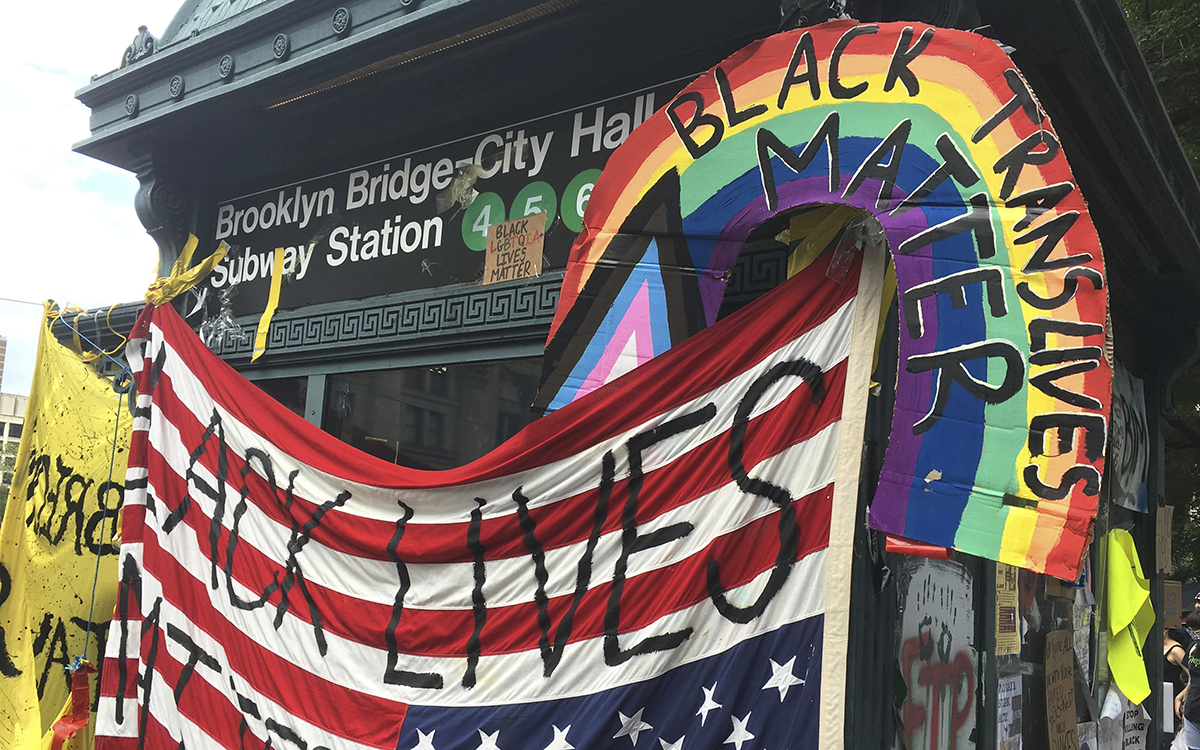

The Environmental Movement Embraces Equity and Social Justice

Like the pandemic and the US elections, the horrific police killings of George Floyd and Breonna Taylor and the historic street protests that followed were not primarily environmental stories. Yet the shockwaves of this year’s racial justice uprising also reverberated into the environmental movement, forcing a long-overdue reckoning about race and justice within some of the country’s oldest green groups.

For decades, the US’s largest environmental organizations have faced criticism that they are too white-dominated and too disconnected from the struggles for environmental justice—which are all too often left to local, underfunded organizations. As Yale professor Dorceta Taylor writes in the next issue of Sierra, “When I researched and wrote The State of Diversity in Environmental Organizations in 2014, I found that minorities composed just 14.6 percent of the staff of environmental organizations.… Meanwhile, people of color make up 38 percent of the US population.”

Environmental groups have sought to address these criticisms by making major investments in equity and inclusion initiatives, prioritizing diversity in hiring, and recommitting to forming partnerships with—and taking leadership from—people-of-color-led frontline organizations.

But it took last summer’s mass protests to accelerate such endeavors and shift them into a whole new level of urgency. Green groups made a point of showing up for Black-led movements for justice as they echoed the call to shift monies away from policing. Then some organizations sought to exhume the skeletons in their closet as a way of demonstrating a commitment to anti-racism. Sierra Club executive director Michael Brune wrote a column apologizing for some early Club leaders’ racist writings and eugenicist beliefs. The Audubon Society had to come clean about the fact that its namesake—famed ornithologist John James Audubon—was a slaveholder.

Such moves are just interim steps in a long-term process. True racial justice, like planetary sustainability, may be forever a work in progress. Yet this year nonetheless marks a decisive break with the past for the American environmental movement, a chance to finally begin prioritizing the connections between a vibrant planet and justice for humans.

Photo by ronnybas/iStock

Congress Passes the Great American Outdoors Act

This tumultuous political year revealed an American electorate that is deeply divided and intensely polarized. Progressives and conservatives, Biden voters and Trump supporters seem to inhabit not just different countries but totally separate universes. Yet there remains one thing that Americans across party lines can agree on: the conservation of lands, waters, and wildlife.

In June, the Senate approved the Great American Outdoors Act, a piece of legislation that permanently allocates $900 million a year to the Land and Water Conservation Fund while also providing additional funding to the National Park Service to deal with a maintenance backlog. The broad-based support for the legislation was just as important as the contents of the measure: The bill had 59 cosponsors in both parties, cleared the Senate by a 73-to-25 margin, and passed the House in a voice vote.

The bill was such a slam-dunk because elected officials across the political aisle know that their constituents support public lands preservation and the protection of wildlife. Annual polling by Colorado College has shown that three-quarters of voters in the West—which is often ground zero for disputes over public lands—want Congress to prioritize public lands preservation ahead of oil and gas drilling, while almost three-quarters support full funding for the Land and Water Conservation Fund (flawed though it may be). As I wrote in a July/August cover story for Sierra, “Even as the peoples of the United States disagree about almost everything, we still manage to agree about the importance of guarding some portion of wild nature. Public lands preservation is an island of consensus in a sea of acrimony—an outcropping from which we might be able to see that some shared values are as enduring as the divisions we fixate upon.”

Such consensus offers a glimmer of hope that elected officials may in the coming year be able to reach agreement on other old-school conservation measures—like, for example, the goal of preserving 30 percent of US lands and waters by 2030. The 30 x 30 goal is supported by Representative Deb Haaland, Joe Biden’s historic pick for interior secretary, and it also enjoys the support of seven in 10 voters in the West, regardless of party affiliation. And the bold 30 x 30 vision is just what this country needs if it’s going to do its part to address the ongoing extinction emergency.

Photo by Fabian Sommer / picture-alliance / dpa / AP Images

The Biodiversity Crisis Is Accelerating

This last one is something of a sleeper story—a topic that is of huge planetary importance yet doesn’t receive a fraction of the media attention it deserves. I’m talking about the continued decline of global biodiversity.

In September, the World Wildlife Fund released the latest version of its Living Planet Report—and the findings were once again grim (perhaps WWF should start titling this the Dying Planet Report?). The WWF found that populations of mammals, birds, fish, amphibians, and reptiles have dropped an average of 68 percent since 1970. In other words: If you are 50 years old, in your lifetime the abundance of wild animals has been cut in two-thirds. Abundance is the key word here, because the problem is not just that we are driving some species to extinction (which we are); we are also reducing the distribution and prevalence of once-common species and, in the process, running the risk of making them functionally extinct in the wild. As WWF puts it, “Our relationship with nature is broken.”

The findings are reason enough to weep—and so is the deafening silence about the unfolding extinction emergency. While the climate crisis is finally receiving the public attention it deserves, the extinction crisis remains in a kind of public-awareness black hole. The incoming Biden administration doesn’t have any articulated plan for dealing with biodiversity loss. And the issue barely registers a blip on the public’s radar. Do a Google search for “climate crisis” and you’ll get 11 million results; do a search for “extinction crisis” or “biodiversity crisis” and you get barely 300,000 results, or about 3 percent as much. All this despite the fact that, as a group of researchers reported in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences last spring, “the ongoing sixth mass extinction may be the most serious environmental threat to the persistence of civilization.”

It’s very demoralizing. Yet hope springs eternal. So here’s to hoping that 2021 may finally be the year in which a combination of citizen advocacy and political leadership reinvigorate the effort to protect all life on Earth—and that in this coming year we find a way to repair our relationship with nature. That would be the kind of good news we all could surely use.

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club