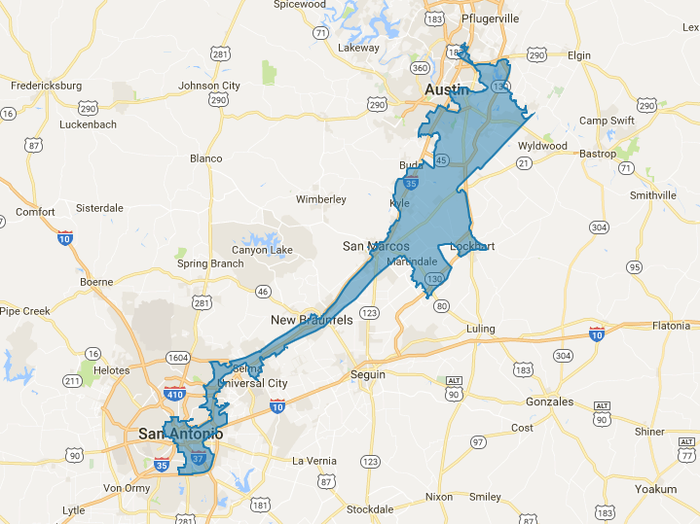

Image: Texas Congressional District 35

By Matt Johnson

The Census hasn’t even started yet, but the process to redraw our legislative and Congressional district maps is already underway. It’s strange. We haven’t even done the “counting” of the Census but the Texas House Committee on Redistricting is already conducting public hearings across Texas to take input about where and who our communities of interest are.

What is a “community of interest”?

It’s not your fantasy football league or book club. It’s basic. It’s fundamental. These are geographically connected communities that share common social or economic interests. Here are some easy ones: people who live in the same city, county, or school district. The League of Women Voters adds that these communities can be people who “share similar living standards, use the same transportation facilities, have similar work opportunities, or have access to the same media of communication relevant to the election process; as well as shared common goals.”

These are all communities of interest that should be kept whole as much as possible in representation in government.

Why does keeping a community of interest whole in district maps matter?

This is the key to representation. People who share a common interests should have the power to represent their shared interest in government. Otherwise, they will be marginalized and left out of key decision making. This is such an incredibly important issue that the Voting Rights Act of 1965 was passed in part to ensure that historically disenfranchised communities, especially African-American communities, are protected from having their interests marginalized.

Other communities of interest

It’s not just political jurisdictions like cities that need to be kept as whole as possible when revising district maps. It is critical to keep communities of color together in district maps as well. But there are many other communities of interest that need to be factored in when redrawing maps. Let’s talk about pollution.

It might not be the first thing that comes to mind when you’re trying to think of your communities of interest. If you’re like me, you are generally trying to think of positive things: my city, my kids’ school district, my neighborhood, etc. The less obvious ones might be things like transportation corridors. If you think about the environment, the first thing that comes to mind might be watersheds. That is a community of interest! Essentially, everyone living on top of the Edwards Aquifer has a shared interest in ensuring that aquifer is protected and preserved.

But in areas of Texas that are disproportionately affected by pollution, it is incredibly important that their representation in the Texas Legislature and Congress reflect their interest in breathing clean air and drinking clean water.

Think of the communities that live on the fenceline of polluting refineries and petrochemical complexes. In some cases, these communities are predominantly low income and communities of color too, and the locations of polluting refineries and complexes were chosen precisely because the political power of these communities was diminished. Fair district maps can help ensure that communities like these can elect representatives that can fight for them.

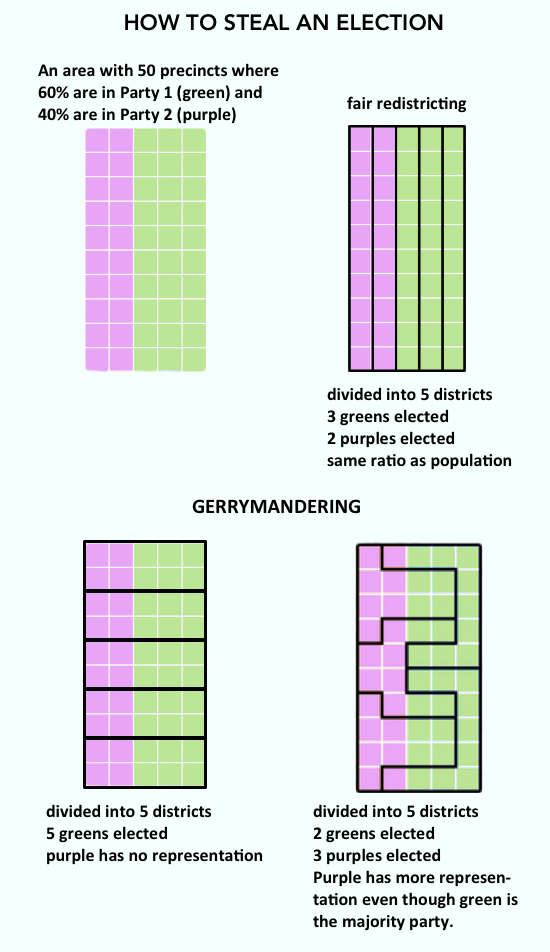

Unfair Districts, aka “Gerrymandering”

Gerrymandering is the opposite of fair redistricting. This is the intentional splitting up of communities of interest to marginalize their political power. In some cases, communities of interest are split up because support for one political party is concentrated in one area. The easiest example of this is Austin. Our capitol city has been likened to a “blueberry in a bowl of tomato soup” (a metaphor that really isn’t accurate anymore, but that’s another topic) because it has reliably voted mostly for Democrats for a long time. The same can be said of other urban areas in Texas: Dallas, Houston, and San Antonio, for example. If district maps were drawn fairly, Austin would have at least a couple Democrats representing it in Congress. But it is represented by a whopping five representatives, and only one of them is a Democrat. That is dilution.

Racial gerrymandering has a long and sordid history, but it still lingers today. This is the intentional splitting up of communities of color to dilute their power. It is illegal, but even recently it has happened (check out what happened in North Carolina).

As someone who is relatively new to a higher level of engagement on redistricting, I really don’t know how much the map makers consider communities that are united by environmental racism and injustice. But I do believe they need to hear about them, and more importantly, know where they are.

The Hearings

Let’s be honest. Those who are aware of redistricting probably do not have a high degree of confidence that any public input would affect the new maps. I’d bet the public confidence in the redistricting process is about as high as thinking you will get in and out of the DMV in less than 15 minutes. It seems like a process too easily corrupted by special interests.

I have those same thoughts… visions of shady backroom conversations, cold and calculated political operatives drafting maps with cutting edge software that secure their hold on power... I’m sure that’s happening.

That can’t stop us though. Texans have to engage in the public meetings and put these communities of interest on the public record despite our low confidence that it will matter, because if we don’t, those special interests can claim these communities were not identified and justify not factoring them in when the new maps are developed.

I think of this kind of like: if you don’t show up, you don’t exist. It stinks. It’s a hurdle and a huge organizing and outreach effort that is arguably outsourced by state government (how much effort is the House Redistricting Committee putting in to making sure everyone knows about these meetings?) and forced onto the public and civil society organizations to ensure people know about them and have opportunities to identify themselves.

Well, now we know about it, and the Sierra Club wants to engage, and help you engage. There are many organizations already working hard to get the word out, train people in how to prepare testimony, and identify important communities of interest that should factor into the creation of new district maps. Some of these groups include the ACLU, League of Women Voters, and the Texas Civil Rights Project.

Here are four things you can do:

- Read up! Read more about the process, how to end gerrymandering, and get involved by going to FairMapsTexas.org. Fair Maps Texas is a coalition of non-profits working together to fix the broken redistricting system in Texas.

- Make a plan! Take a look at the League of Women Voters redistricting toolbox (which includes this awesome testimony guide - a great planning resource if you’re ready to attend a hearing) to learn more about how you can get involved in the redistricting process. Fair Maps Texas also organizes training sessions across the state.

- Make your voice heard! Attend a public hearing on redistricting and share your thoughts and get them on the record! Here’s a list of tentative hearing dates and locations.

- Stay in touch! We want to hear from you about your experience, and your thoughts about redistricting and how it affects our ability to address environmental injustice. Sign up here.

More to come.

Please consider making a donation to the Sierra Club's Lone Star Chapter so we can continue to fight for clean water, clean air, protecting our treasured green spaces in Texas.