Mining — the extraction of minerals from the earth — has deep roots in Wisconsin. For millennia, Native Americans living near Lake Superior used the region’s abundant copper supply to forge tools, weapons, and jewelry, developing what is now called the Old Copper Culture. And beginning in the early 1800s, Wisconsin’s accessible lead deposits in the southwest part of the state attracted immigrants and helped to fuel the nation’s early growth.

But, by the mid-to-late 1800s, the pervasive harms of mining became apparent. Mining has been historically unsustainable — both in regard to the economy and to the environment. As an exploitative industry that relies on extracting a finite amount of raw materials from the earth and hoarding the wealth that’s produced, it generally leads to brief spurts of inequitable economic growth followed by inevitable crashes and periods of depression. Once they’ve depleted the local supply of minerals and exhausted the area’s resources, large mining companies often move jobs elsewhere and abandon the towns that once hosted them — fueling a pernicious cycle of boom-and-bust that ultimately devastates local communities. One reason metallic mining has declined in Wisconsin is because mining companies have already exhausted all the high-grade deposits, leaving only uneconomic sites remaining.

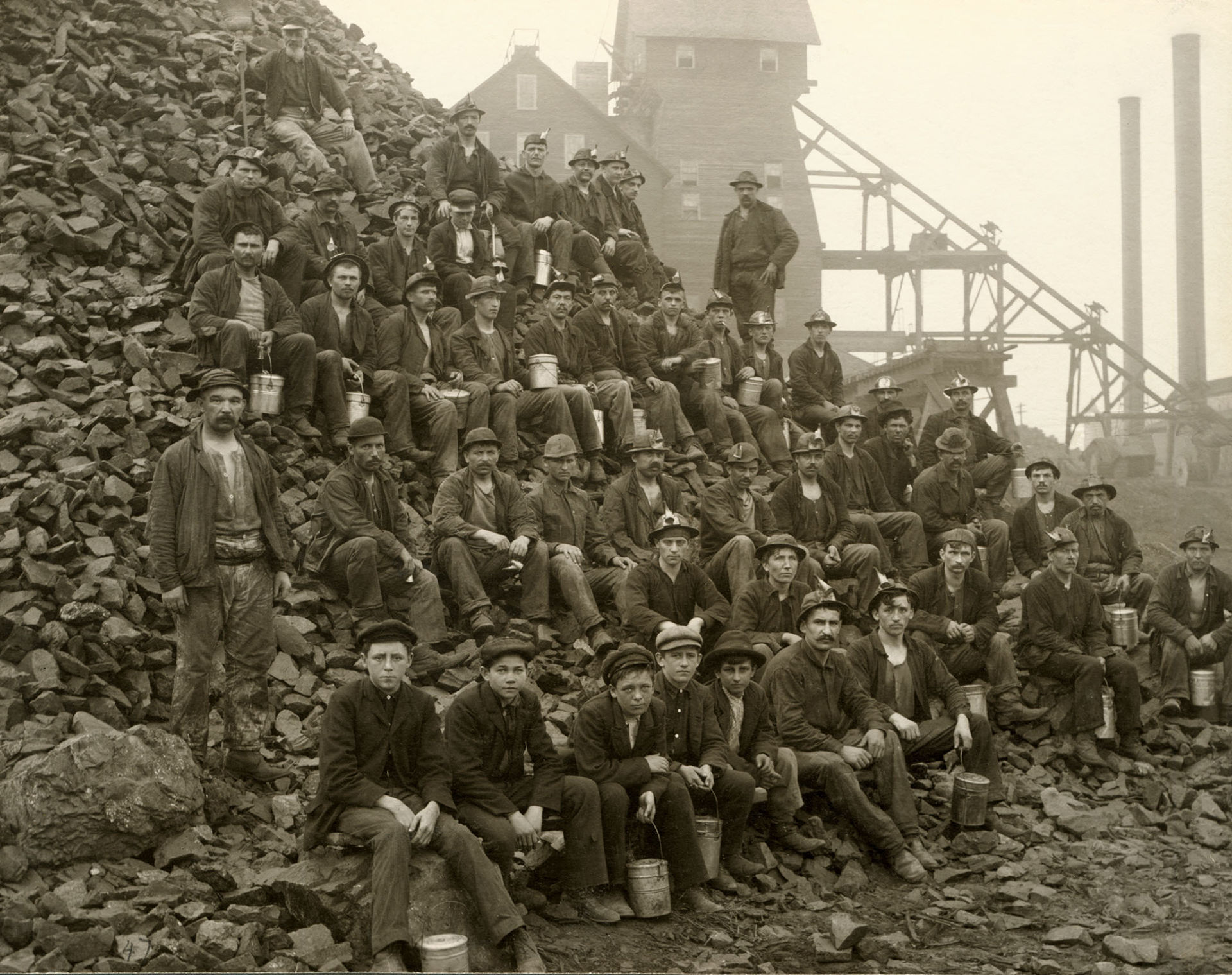

Environmentally, things looks even worse — mining operations often pollute both ground and surface waters with toxic chemicals used in the mineral extraction process and release corrosive acids that leach waste and harmful substances from the mine into waterways (called acid mine drainage). They also generate unhealthy amounts of air pollution as well as disrupt ecosystems, often by clearing pristine forests and poisoning bodies of water. Plus, abandoned mines and their associated toxic waste often necessitate extensive and expensive storage and cleanup efforts. But the harms don’t stop there — mining also represents a public health disaster. Nearby communities must cope with water that’s been contaminated with heavy metals like arsenic and lead, as well as other toxic substances, that lead to serious health problems like cancer and neurological damage. Miners also often suffer from higher rates of disease acquired during exposure in the mines, and companies often cut corners on safety and allow dangerous working conditions — leading to fatal accidents.

Environmentally, things looks even worse — mining operations often pollute both ground and surface waters with toxic chemicals used in the mineral extraction process and release corrosive acids that leach waste and harmful substances from the mine into waterways (called acid mine drainage). They also generate unhealthy amounts of air pollution as well as disrupt ecosystems, often by clearing pristine forests and poisoning bodies of water. Plus, abandoned mines and their associated toxic waste often necessitate extensive and expensive storage and cleanup efforts. But the harms don’t stop there — mining also represents a public health disaster. Nearby communities must cope with water that’s been contaminated with heavy metals like arsenic and lead, as well as other toxic substances, that lead to serious health problems like cancer and neurological damage. Miners also often suffer from higher rates of disease acquired during exposure in the mines, and companies often cut corners on safety and allow dangerous working conditions — leading to fatal accidents.

Recognizing the detrimental consequences of mining, the Wisconsin legislature passed important and comprehensive mining legislation in the early 1980s that recognized that all forms of metallic mining, whether iron, copper, lead, zinc, or precious metals, harm the environment (especially due to acid mine drainage) and have significant impacts to local communities due to its boom-and-bust nature. But before the Prove It First law (also known as the Mining Moratorium law) was approved, the state challenged the mining industry to give one example of a metallic sulfide mine that had been safely operated and closed without polluting the environment. Predictably, the industry has failed to identify a single example to this day.

In a 1995 report, Wisconsin’s DNR confirmed the inherent destructive nature of mining, writing: “There are no ideal metallic mineral mining sites which can be pointed to as the model approach in preventing acidic drainage industry-wide.” As a result, the Wisconsin State Legislature approved the Mining Moratorium Law by overwhelming bi-partisan margins (29-3 in the Senate and 91-6 in the Assembly), and Governor Thompson signed it into law in 1997. In order for a company to obtain a permit to mine, the law requires that it identify an example of a metallic sulfide mine that didn’t pollute the environment while it was operating and after it closed. The law received widespread praise from environmental groups and concerned citizens, and it helped preserve Wisconsin’s bountiful yet fragile natural resources for more than a decade.

Within recent years, however, industry lobbyists and some elected officials have attempted to dismantle these mining regulations that have protected our state, with the aim of ramping up destructive mining practices. In 2013, after a hard-fought battle, industry insiders forced a bill through the legislature that demolished environmental safeguards related to mining, eliminated public input, reduced revenues to local communities, and rushed the permit review process, and Gov. Walker quickly signed it into law. Unfortunately, this was just the beginning. After a series of other bills curbed local governments from enacting regulations to control mining and reduced other general environmental protections related to mining, the legislature finally repealed the Mining Moratorium law in 2017.

Within recent years, however, industry lobbyists and some elected officials have attempted to dismantle these mining regulations that have protected our state, with the aim of ramping up destructive mining practices. In 2013, after a hard-fought battle, industry insiders forced a bill through the legislature that demolished environmental safeguards related to mining, eliminated public input, reduced revenues to local communities, and rushed the permit review process, and Gov. Walker quickly signed it into law. Unfortunately, this was just the beginning. After a series of other bills curbed local governments from enacting regulations to control mining and reduced other general environmental protections related to mining, the legislature finally repealed the Mining Moratorium law in 2017.

Responsible mining requires sound planning to mitigate the economic, social, and environmental impacts of large-scale raw material extraction, and, without proper regulations in place, the state is at the mercy of mining corporations that seek to exploit our natural resources and pollute our environment — all to line their own pockets at the expense of public wellbeing. Despite these recent setbacks, we’re still working to implement more sustainable and stringent regulations, and we’ll continue to fight against these special interests to protect all of Wisconsin.

To learn more about mining in the state (and to hear about some recent success stories!), please check out the following pages: