As the fossil fuel industry intensifies extraction of tar sands oil in the landlocked Athabasca mines, it needs to figure out ways of transporting more and more of this oil to refineries for further processing and to seaports for export. While oil can be shipped via truck and rail, pipelines offer the most cost-efficient mechanism for transporting massive quantities of oil over great distances by land — and this is where Enbridge comes in.

As the fossil fuel industry intensifies extraction of tar sands oil in the landlocked Athabasca mines, it needs to figure out ways of transporting more and more of this oil to refineries for further processing and to seaports for export. While oil can be shipped via truck and rail, pipelines offer the most cost-efficient mechanism for transporting massive quantities of oil over great distances by land — and this is where Enbridge comes in.

Enbridge specializes in “energy delivery,” according to its website, and this euphemistic phrase basically means it pumps fossil fuels through a massive web of pipelines for billions in profit (nearly $4 billion in 2018 to be precise). As the supply of tar sands oil increases, Enbridge wants to pump more oil — meaning it has to either construct new pipelines or expand the capacity of its existing pipelines. In Wisconsin, it wants to do both.

Line 61 Expansion

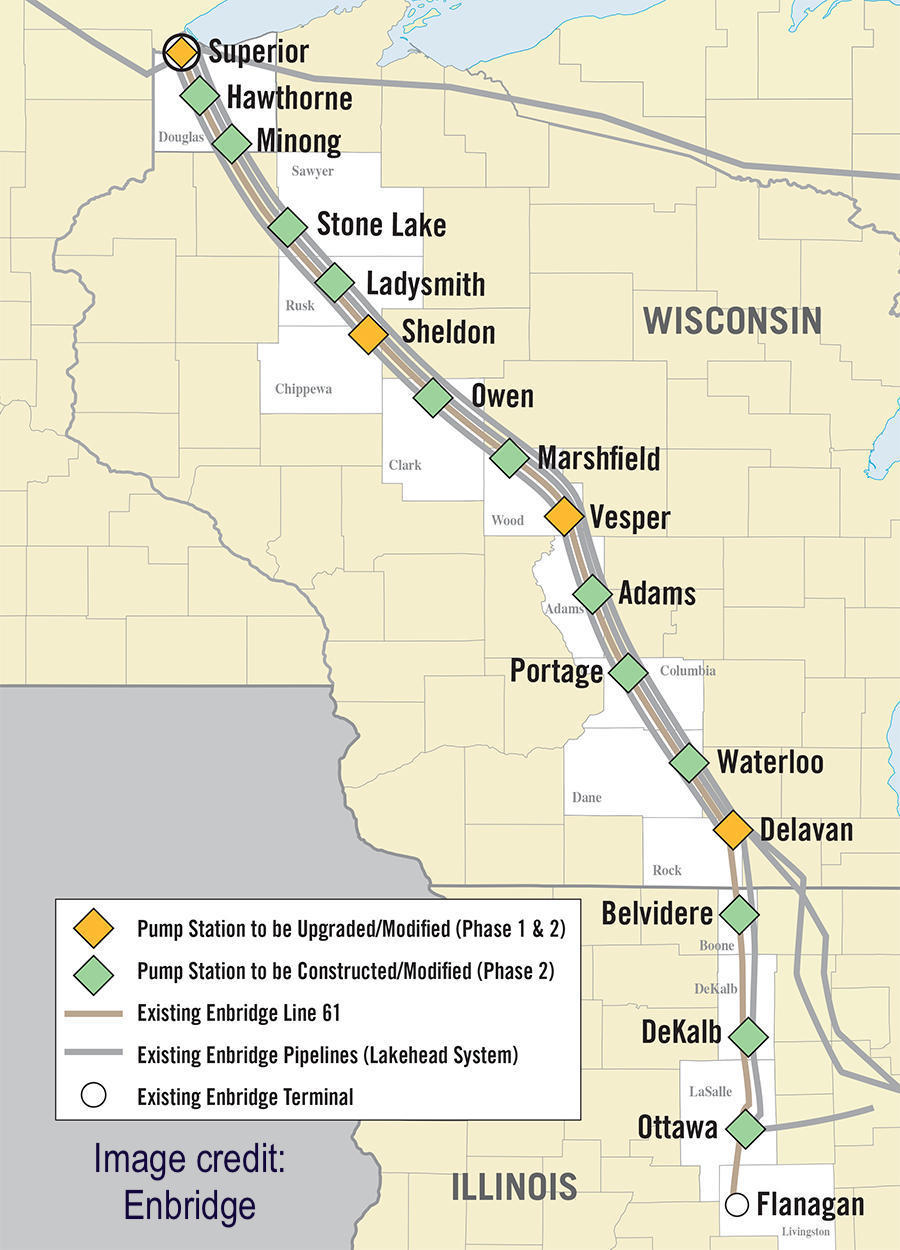

Built just over a decade ago but following the same route as other older lines, Line 61 slices diagonally across the entire state of Wisconsin — from the City of Superior in the northwest to the area near Janesville and Beloit in the south. It runs more than 300 miles, cutting through residential areas, family farms, businesses, private lands, important waterways (including a staggering 240 rivers and streams), and national forests, as well as skirting close to tribal land.

Despite being constructed to carry 400,000 barrels of oil each day, Enbridge announced in 2012 its intention to triple capacity by forcing 1.2 million barrels through the pipeline per day by adding new pumping stations to increase flow rate, exacerbating the risk of catastrophic ruptures. Environmental organizations, tribal groups, and landowners resisted the move — demanding more accountability, community input, and attention to environmental concerns. For residents whose homes lie near the pipeline, a spill would be catastrophic — unleashing toxic tar sands oil (which is much more difficult and costly to clean than conventional oil) and other hazardous chemicals onto their properties. But Enbridge ignored these protests and pressed onward, and the state of Wisconsin let it happen; the state DNR approved the proposed expansion in 2014, without even conducting a new environmental impact analysis to gauge the possible hazards to the environment.

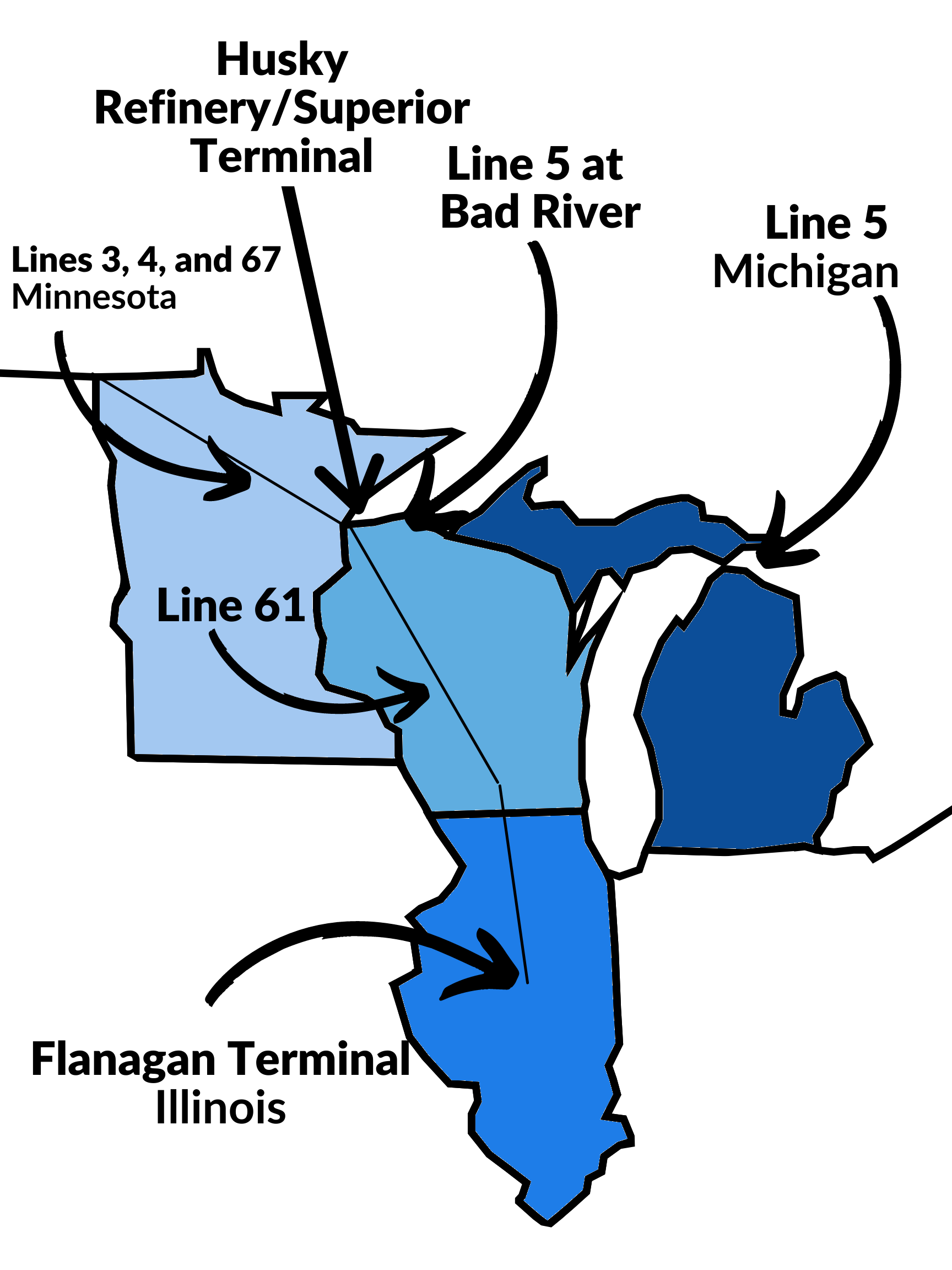

Line 61 could also be facing another expansion. The Illinois EPA is reviewing permits for Enbridge to make structural and operational changes to the Flanagan Terminal, a pipeline facility in Illinois that Line 61 connects to. These changes would increase the capacity of the terminal, opening up the possibility of increasing the carrying capacity of Line 61. If Enbridge also succeeds in increasing the carrying capacity of two more pipelines, Line 4 and 67, which feed Line 61 from Minnesota, then Line 61 would become the largest tar sands pipeline in North America by carrying over 1.2 million barrels a day.

Dane County vs. Enbridge

Following this development, concerned citizens pressured Dane County to address the proposed expansion. While legally unable to prohibit Enbridge’s scheme outright, the county decided to protect its land and communities from possible environmental devastation by requiring that Enbridge take out $125 million in insurance on the pipeline to cover the potentially costly cleanup. Line 61, despite being relatively new, has already had several major spills, so Dane County residents were understandably alarmed by Enbridge’s proposal to triple the line’s capacity. Enbridge also has notoriously suffered from a terrible safety record and a series of major pipeline disasters, including one that caused more than a billion dollars in damages near Kalamazoo, Michigan — when operators ignored warning signs and overrode automatic emergency shutoffs that allowed oil to flood out of the pipe for 17 hours. Even when Enbridge built Line 61, it damaged sensitive ecosystems, received more than 100 violations, and was forced to pay more than $1 million in fines.

Enbridge, however, refused to cooperate with Dane County, appealed the requirement, and increased capacity anyway, while simultaneously lobbying the state to prevent Dane County from forcing it to buy insurance. These efforts paid off — in the 2015 state budget, the legislature at the last minute snuck in an amendment that banned local governments from requiring that pipeline companies purchase additional pollution insurance, blatantly targeting Dane County. Enbridge then sued Dane County, while landowners sued Enbridge. This erupted into an extended legal battle. Unfortunately, in 2019, the Wisconsin State Supreme Court ruled in Enbridge's favor in a decision that sparked controversy and calls of corruption. Despite this disappointing news, we've still been enormously successful — derailing Enbridge's plans, costing them money, and galvanizing Wisconsin communities against the pipeline.

Enbridge, however, refused to cooperate with Dane County, appealed the requirement, and increased capacity anyway, while simultaneously lobbying the state to prevent Dane County from forcing it to buy insurance. These efforts paid off — in the 2015 state budget, the legislature at the last minute snuck in an amendment that banned local governments from requiring that pipeline companies purchase additional pollution insurance, blatantly targeting Dane County. Enbridge then sued Dane County, while landowners sued Enbridge. This erupted into an extended legal battle. Unfortunately, in 2019, the Wisconsin State Supreme Court ruled in Enbridge's favor in a decision that sparked controversy and calls of corruption. Despite this disappointing news, we've still been enormously successful — derailing Enbridge's plans, costing them money, and galvanizing Wisconsin communities against the pipeline.

In fact, it hasn’t all been smooth sailing for Enbridge, thanks to stiff opposition from a grassroots coalition of concerned residents. From Honor the Earth to 350 Madison to Wisconsin Safe Energy Alliance to our very own Wisconsin chapter of the Sierra Club, nonprofits have been fighting against Enbridge’s octopus-like stranglehold on North America to protect us all from the dangers of tar sands oil pipelines — not just in Wisconsin but also in neighboring states, nearby provinces, and in the rest of the United States and Canada. Community members, landowners, and tribes have risen up to take on the fossil fuel giant — engaging in direct action protests, attending zoning board meetings and public hearings, waging ongoing legal battles, and donating their precious time and resources to the cause.

As Enbridge continues to jeopardize the health and prosperity of our state by pushing more toxic tar sands through the pipeline, we must band together to defend Wisconsin. The fight is far from over.

Line 66

Beyond increasing existing capacity, Enbridge’s scheme to push more tar sands oil through Wisconsin also entails the possible construction of a new line. In 2014, Enbridge began surveying land in the vicinity of Line 61, and shortly afterward it announced to investors about potentially “twinning” Line 61 by adding another pipeline — Line 66 — along the same corridor. Additionally, it has received permits and continues to invest in bringing more oil into Wisconsin, which would necessitate building a new line to transport the new oil out of the state.

In 2015, Enbridge successfully lobbied the state of Wisconsin to change eminent domain laws to make it easier for the company to usurp private land to construct the new pipeline. Currently, Enbridge has an easement to use an 80 feet wide corridor that runs 300 miles across Wisconsin. But there’s not enough room in the crowded corridor — which already contains four lines — to construct a new pipeline, meaning Enbridge would need to confiscate more land from nearby property owners to build Line 66.

In 2016, Enbridge presented a plan for the new Line 66 to shareholders, and in late 2017 it further detailed its proposed plan to add a new pipeline along the existing route in a report, among other options. Meanwhile, Enbridge has been contacting landowners along the route, collecting information about the properties, and performing other development work. It has even been presenting the communities along the route with small gifts and donations in an effort to “buy goodwill” while simultaneously clearing property — often against landowners' wishes — near the corridor.

Throughout this whole process, however, Enbridge has repeatedly denied its plans to construct the pipeline when confronted by community members, even sending letters to all landowners near the corridor explaining that: “At this time, no expansion project has been approved.” Its website also stated for a long time: “Enbridge does not have a new pipeline project in Wisconsin.”

But community members, landowners, indigenous groups, and environmental organizations are skeptical, and rightfully so. Enbridge has a history of deception and disreputable practices, and, while it currently does not have a project, that doesn’t mean there won’t be one in the near future. Enbridge’s carefully worded statements do not preclude a new pipeline, they just insist there isn’t one being built at this very moment. Part of this denial may stem from the fact that the new Wisconsin pipeline is contingent on what happens in neighboring states, including Minnesota and Michigan. Activists in Minnesota have attempted to halt Enbridge’s replacement of Line 3, and recently scored a legal victory against the project, although its fate is still to be determined. Line 3 would supply Wisconsin with more tar sands oil, so Line 66 might depend on Line 3’s construction. Additionally, officials in Michigan are seeking to shut down Line 5, which runs through the Upper Peninsula of Michigan and under the Straits of Mackinac. It poses tremendous risks to the Great Lakes, and closing it would be a tremendous environmental victory. But without Line 5 in Michigan, Enbridge might decide to send more oil through Wisconsin.

But community members, landowners, indigenous groups, and environmental organizations are skeptical, and rightfully so. Enbridge has a history of deception and disreputable practices, and, while it currently does not have a project, that doesn’t mean there won’t be one in the near future. Enbridge’s carefully worded statements do not preclude a new pipeline, they just insist there isn’t one being built at this very moment. Part of this denial may stem from the fact that the new Wisconsin pipeline is contingent on what happens in neighboring states, including Minnesota and Michigan. Activists in Minnesota have attempted to halt Enbridge’s replacement of Line 3, and recently scored a legal victory against the project, although its fate is still to be determined. Line 3 would supply Wisconsin with more tar sands oil, so Line 66 might depend on Line 3’s construction. Additionally, officials in Michigan are seeking to shut down Line 5, which runs through the Upper Peninsula of Michigan and under the Straits of Mackinac. It poses tremendous risks to the Great Lakes, and closing it would be a tremendous environmental victory. But without Line 5 in Michigan, Enbridge might decide to send more oil through Wisconsin.

As a result, grassroots groups have begun getting prepared and mounting their defenses to protect the environment, their homes, and indigenous rights from the pervasive harms of a potential new pipeline. After Enbridge announced its intention to expand, 80 Feet Is Enough! formed to protest Enbridge’s potential land conquest through the exploitation of eminent domain laws, which were originally intended to facilitate governmental actions to promote public wellbeing — not to advance private special interests and foreign companies in their pursuit of profit. Enbridge already has control of 80 feet of local landowners’ property, and if it decides to construct Line 66, it could require up to 300 feet. This means affected families and landowners could immediately lose their homes, farms, and other property near the pipelines, not to mention face the risk of toxic spills and the ensuing environmental degradation and lower property values. Likewise, the Wisconsin Easement Action Team (WEAT) was established to protect landowners from Enbridge’s expansions, and the Wisconsin Safe Energy (WiSE) Alliance formed to stop Enbridge’s plans and rally affected community members.

Hearing the stories of affected residents is perhaps the most compelling way to understand the human costs of these pipelines. In a series of videos, WiSE interviewed landowners about their experiences dealing with Enbridge and its attempted land grabs to expand its massive web of pipelines — exploiting “eminent domain for private gain.” Darcy, who would most likely lose her house if Enbridge builds a new line, explains, “They just decide what they’re gonna take, and then they just take it.” An Enbridge agent showed up at her house and told her he would need to clear part of her property for “temporary access.” When she asked if they could spare some of it, the Enbridge agent replied, “This is not a negotiation.” Enbridge then proceeded to chop down all of her 200-year-old oak trees. And this isn’t an isolated event. Another resident, Lorene, had a strikingly similar experience: “My husband came home from work one day and was mortified to see trees laying down all over…[The workers had] stayed at the edge of the easement until they were visually passed the corner of the house, and stepped over it and just mowed down every tree that was there.” After she protested, an agent declared, “We’re gonna take the entire 100 feet [cutting down over 400 trees for temporary workspace] and we’re gonna give you nothing, and we’re not taking out the stumps.”

Hearing the stories of affected residents is perhaps the most compelling way to understand the human costs of these pipelines. In a series of videos, WiSE interviewed landowners about their experiences dealing with Enbridge and its attempted land grabs to expand its massive web of pipelines — exploiting “eminent domain for private gain.” Darcy, who would most likely lose her house if Enbridge builds a new line, explains, “They just decide what they’re gonna take, and then they just take it.” An Enbridge agent showed up at her house and told her he would need to clear part of her property for “temporary access.” When she asked if they could spare some of it, the Enbridge agent replied, “This is not a negotiation.” Enbridge then proceeded to chop down all of her 200-year-old oak trees. And this isn’t an isolated event. Another resident, Lorene, had a strikingly similar experience: “My husband came home from work one day and was mortified to see trees laying down all over…[The workers had] stayed at the edge of the easement until they were visually passed the corner of the house, and stepped over it and just mowed down every tree that was there.” After she protested, an agent declared, “We’re gonna take the entire 100 feet [cutting down over 400 trees for temporary workspace] and we’re gonna give you nothing, and we’re not taking out the stumps.”

Another resident, Jason, woke up one morning to the sounds of Enbridge crews excavating his property due to an oil leak, which ended up contaminating his land. After that, he needed frequent water quality tests to ensure that his drinking water had not been contaminated. And that’s not the worst of it. “Enbridge plans on taking an additional 300 feet of our land,” he said. “If we go to the west, it takes away a part of my house; it’ll take away my garage. If we go to the east it takes part of my woods and potentially takes my neighbors’ house.”

Another resident, Jason, woke up one morning to the sounds of Enbridge crews excavating his property due to an oil leak, which ended up contaminating his land. After that, he needed frequent water quality tests to ensure that his drinking water had not been contaminated. And that’s not the worst of it. “Enbridge plans on taking an additional 300 feet of our land,” he said. “If we go to the west, it takes away a part of my house; it’ll take away my garage. If we go to the east it takes part of my woods and potentially takes my neighbors’ house.”

These stories again make it clear that we need to protect our residents and the environment from Enbridge’s destructive aims. It may have the initial upper hand in that it is a massive centralized company with more than $125 billion in assets, powerful allies in government, and vast legal resources at its disposal, but we have the numbers, the passion, the public support, and nature on our side. Through community organizing and collective action, we can capitalize on our strengths and challenge this irresponsible fossil fuel giant and defend our environment.

If you’d like to help us out and be a part of the coalition that takes on Enbridge and protects our state, please volunteer with us! Or contact Katie Hogan for more information.